NYU history professor Greg Grandin discusses the history of the concept of national sovereignty as it originated in Latin America, but was repeatedly challenged by the US. The latest US threats against Venezuela once again threatens to make the concept irrelevant and would serve as justification for more unilateral interventions

Story Transcript

GREG WILPERT: It’s The Real News Network, and I’m Greg Wilpert, coming to you from Baltimore.

President Donald Trump held an important rally in Miami, Florida last Monday in which he once again threatened Venezuela with military intervention and called on the Venezuelan military to rise up against President Nicolas Maduro.

DONALD TRUMP: We seek a peaceful transition of power, but all options are open. We want to restore Venezuelan democracy and we believe that the Venezuelan military and its leadership have a vital role to play in this process. If you choose this path, you have the opportunity to help forge a safe and prosperous future for all of the people of Venezuela, or you can choose the second path, continuing to support Maduro. If you choose this path, will find no safe harbor, no easy exit, and no way out. You will lose everything.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

GREG WILPERT: Meanwhile, Venezuela’s self-proclaimed and so-called interim president, Juan Guiado, announced that his parallel government will organize a humanitarian aid corridor from Colombia to Venezuela this coming Saturday on February 23.

Joining me now to discuss Trump’s most recent threats against Venezuela is Greg Grandin. Greg is Professor of History at New York University and is the author of many books. He recently wrote an important article for The London Review of Books, titled, “What is at Stake in Venezuela?” Thanks for joining us today, Greg.

GREG GRANDIN: Thanks for having me, Greg.

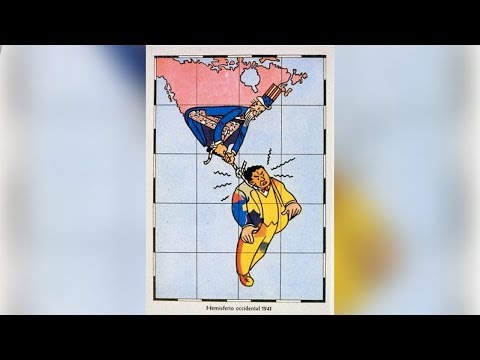

GREG WILPERT: So your article suggests that what’s at stake in Venezuela is basically the concept of sovereignty, and you provide a history of the concept. As we saw from the clip of Trump’s speech on Monday, he clearly did not give a moment’s thought to the issue of Venezuelan sovereignty. Give us a brief rundown of how the concept evolved in Latin American history and how we got to where we are now, with Trump openly saying that a coup or U.S. military intervention in Venezuela are the only options left for Maduro.

GREG GRANDIN: The idea of national sovereignty, that a country’s leadership and constituted government have authority, monopoly authority, over its people and territory, it’s an idea that has deep roots in Western thought. But it was really in Latin America, Spanish America and Brazil, where it was actualized after the wars of independence in the early 1800s. So all of these Spanish-American republics came into the world both challenged and legitimated by their neighboring countries. What came into the world was an already existing unity of nations, a league of nations. And in order to survive, they recognized that they needed to recognize the sovereignty of each other. Each country legitimated the other in the sense that they overthrew royal monarchical rule and claimed the right to independence.

But they threatened each other, because under the terms of international law, nations had the right to conquest and they had the right to wage war, an aggressive war, and keep territory that they obtained during the military conquest. So they set about revising international law. And it’s a long story, but basically, the concept of national sovereignty emerges in this context. But also vis a vis the United States, not only did they have to contend with each other, all of these nations, Colombia and Venezuela and Alto Peru and Chile and what became Argentina and Uruguay, they also had to contend with the United States. And the United States was moving across the west like a whirligig, waging war on Mexico, soon to wage war on Spain to take Puerto Rico and Cuba.

And so, Latin American jurists, politicians, and intellectuals deepened their commitment to the ideal of sovereignty, and they constantly tried to force the United States to accept that as a legitimate international law. The U.S. refused until 1933. In 1933 there’s an international conference in Montevideo. And just to make a long story short, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration conceded to Latin America’s long-standing demand that it would not interfere in internal or external affairs of other Western Hemispheric nations. And rather than leading to recession of U.S. power, this actually helped the United States find new, multilateral ways of creating an international community where it could project its power free of the burdens of direct militarism and direct colonialism.

And for decades, the ideal of sovereignty undergirded a kind of multilateral law in the international community, what became the United Nations, what became the Organization of American States. That begins to become undermined in Latin America in the 1980s with the rise of the new right in the United States and the assault on Nicaragua. We can go through the list all the turning points, but the invasion of Panama is an important turning point that undermined sovereignty. What I was trying to get at it that essay was that it’s complicated, there are contradictions within the ideal of sovereignty. What do you do with a sovereign leader who is unjust to his own people? But the opposite is also true in liberal interventionism in the name of some higher ideal, obviously has created its own problems, as we see in Iraq and Libya and Afghanistan.

GREG WILPERT: I want to return to that in a moment. But before that, what would you say are the main reasons that the concept of sovereignty has eroded over the past few decades? I would say especially since Nixon and Kissinger’s overthrow of Chile’s president, Salvador Allende, in 1973.

GREG GRANDIN: Well, Allende was a covert operation, so it wasn’t a direct ideologic assault on the concept of sovereignty. The United States intervened in Latin America through the Cold War during all these periods, and they either did it covertly, where it didn’t entail a legal revision of sovereignty, as in Chile in 1973, or they managed to corral the OAS, or in the case of Grenada in 1983, the Association of Eastern Caribbean Nations, into giving a multilateral stamp of approval on the intervention. It’s really not until Panama that you see a full-on assault on the idea of sovereignty, even against–because the OAS was completely against the invasion of Panama.

So to go back to your question, what begins to erode it is the demise of the Soviet Union, the ascension of the United States as sole superpower, the beginning of the unraveling of the Keynesian political economic order, the rise of the human rights movement, the rise of the Right to Protect movement with international law. So you can look for causation, what’s cause and what’s effect. Of all of those things that account for the erosion of sovereignty. But there has been an undermining of the idea. But it’s still very precious in Latin America for historical reasons. The left, and beyond the left, is still very committed to the ideal of national sovereignty.

GREG WILPERT: Now, in referring to that the 1989 invasion of Panama in order to get Manuel Noriega, you say that it had a transformative effect on international law. And actually, I think in your article you suggest also that it paved the way for the invasion of Iraq. Now, do you think the effort to oust Maduro in Venezuela could pave the way for other interventions?

GREG GRANDIN: Well, certainly. I mean, Trump said it the other day. In the queue is Cuba and Managua, and it’s fairly clear at the same time that they’re trying to build a coalition to raise the ante with Iran. I mean, this is a classic case in which it’s an attempt to use a foreign policy crisis to reorder the international community. It’s laying down a marker for China, laying down a marker for the Soviet Union–not the Soviet Union, sorry–laying down a marker for Russia. It’s trying to marshal its new allies in Latin America, particularly Bolsonaro in Brazil and right wing governments in Colombia and Argentina. At the same time, it’s being used domestically to keep neoconservatives within the Trump coalition, keep Florida within the Trump coalition as we go to 2020. And it’s also used to set the terms for the 2020 election.

I like to say foreign policy is the place where hegemony is created not over other countries, but within this country. So when Trump immediately pivots from Venezuela to Alexandria Ocasio Cortez and Bernie Sanders, and says America will never be a socialist country, what he’s doing is he’s invoking our whole world view that has very deep resonance, while at the same time laying out the terms of how he hopes to the fight in the 2020 campaign. So the Venezuela push that’s happening, there’s lots of different levels in which it’s taking place.

GREG WILPERT: Now finally, very quickly, it seems that many governments in the Americas, especially the so-called Lima group of twelve conservative governments plus Canada are wholeheartedly endorsing this readdition of what one might call the reloaded Monroe Doctrine. And as you outline in your article, in the past, the governments of Latin America has mostly rejected U.S. assertion of a right to violate their sovereignty. What do you think has changed, that they would side with U.S. now in the case of Venezuela?

GREG GRANDIN: Well, there has been a rollback of the red tide, right, the pink tide, the developmentalism that started with Chavez and started with Aristide in some ways in Haiti. And so, there’s been a kind of complete pushback of all of that. I mean, it’s not unprecedented. All of the OAS lined up with Washington to sequester Cuba in the early 1960s, so there is there is a history of this. What is unique about it, I think, is the division, that it’s not all of Latin America. All of Latin America lined up against Cuba on the side of Washington back in the day. Now we’re seeing some real divisions, mostly in Mexico, but Uruguay, Bolivia, and I think that that’s what’s more historically significant, that the United States has regained the ability to kind of reassert its power via Monroe Doctrine-like coup attempts that don’t even have the fig leaves of legitimacy in some ways.

But on the other hand, it’s doing it in a way that deepens divisionism within the region, which I think, frankly, could be dangerous. I mean, of the things, for good or bad, about the United States and Latin America, is that the United States tended to treat Latin America as a coherent region. It didn’t play the politics of divide and rule that much for whatever reason. So therefore, there hasn’t been a lot of interstate wars within Latin America. And so, now we’re seeing a kind of breakdown of that historical unification over Venezuela, which who knows how it will play out.

GREG WILPERT: OK. Well we’re going to leave it there. I was speaking to Greg Grandin, Professor of History at New York University. Thanks again, Greg, for having joined us today.

GREG GRANDIN: Thank you so much, Greg. It’s great to be in.

GREG WILPERT: And thank you for joining The Real News Network.