On Transgender Day of Remembrance, Sylvia Rivera Law Project founder Dean Spade talks about the lack of federal protections for trans people and how communities are fighting back at the local level

Story Transcript

DHARNA NOOR: It’s The Real News. I’m Dharna Noor in Baltimore.

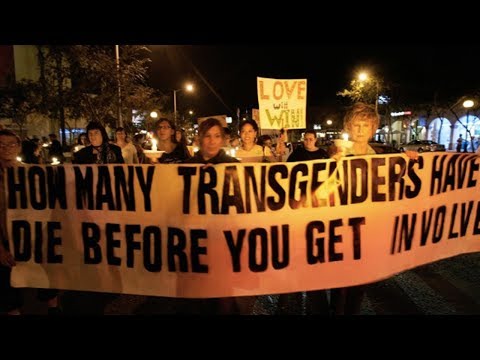

November 20, millions across the world observe Transgender Day of Remembrance to give respect to trans lives lost that year. The day was founded 18 years ago to honor a trans woman sex worker Rita Hester, who was murdered in Massachusetts. A Human Rights Watch report shows that this year alone, at least 22 trans people have been murdered in the U.S. so far. 82 percent of them were women of color. This year, the day comes amid what many are calling attacks on transgender protections from the Trump administration. On Sunday, the Washington Post reported that the administration told divisions of the Department of Health and Human Services not to use certain terms in official budget documents for 2019. One of those words is transgender. Another one is diversity. And last month the New York Times leaked a memo from the Department of Health and Human Services showing the intent to establish a legal definition of sex as fixed, biological, and determined at birth.

Here to talk about all of this is Dean Spade. Dean is an associate professor at Seattle University School of Law. In 2002 he founded the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, a nonprofit that provides free legal help to low-income people and people of color who are trans, intersex, and/or gender nonconforming. Thank you so much for being here today.

DEAN SPADE: Thanks for having me.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

DHARNA NOOR: So I guess we should just take a minute to reflect first. I mean, 22 trans people killed this year so far; last year a record-breaking 27 trans people were killed. And in a piece you wrote for Truthout last month you argue that the right wing’s attempts to erase transgender protections and trans people could lead to more trans people dying and struggling, especially poor transgender people and trans people of color. How, and why?

DEAN SPADE: Yeah, and I think–there’s a couple of things. First, I would say that when we look at the number of 22 trans people killed, that is so profound and so heartbreaking, but we also need to really think about all the life-shortening conditions that trans people face. Right now all across the United States, trans women are living in men’s prisons and detention centers. Trans people have extremely high rates of homelessness and poverty; 29 percent of trans people are living in poverty compared to 14 percent of the U.S. population. And when you look at people of color, trans people of color, you get into rates of 40 percent or more.

So the kinds of things that shorten your life, like not having access to healthcare, being homeless and living under the stress of that, experiencing discrimination, spending time locked up and not having the basics that you need in terms of nutrition and healthcare, all of those things are leading–are producing a lot of trans death that we can’t even see just in the homicide statistics, which of course are already devastating. So I just want to sort of lift that up.

I think that the memo that was leaked that the Trump administration is, you know, planning some kind of redefining of sex is really important in some ways that maybe not everyone understands. One thing that’s I think really significant is that in the United States there actually is no federal definition of gender. So every state agency and government body that you deal with has its own way of defining gender, whether it’s the DMV in your state, or the Department of Health in the state where you were born, maybe, or how the prison manages people, or how the local shelters manage people. All of those places have different ways that they determine gender and that they do or don’t let trans people be marked as the person sees themselves. And one of the sort of key strategies of trans activists for the last at least 20 years especially has been trying to improve all those local policies and practices so that trans people can be more well, can have a piece of ID that matches who we say we are so we don’t have as much trouble with the police, maybe; just get through life and not deal with some of the kind of the worst exclusions and violence.

So the danger, I think one danger of this signal from the Trump administration about some kind of federal definition that might sort of be released through federal agencies is that that would impact all those local fights that we’re doing, often at a very local or municipal level, because it’s a huge signal from the federal government to say, you know, this is what we think it is, and it’s the most retrograde definition possible from the perspective of trans people’s survival.

So that’s truly disturbing, both because it we might see it unroll–and a lot of local and state programs get federal funding. It might in some way impact them directly. And also because when something like that comes down even just in the news without having been implemented yet legally, you see changes happen in the lives of people who are dealing with some of the worst conditions. So trans people who are in the welfare office who are trying to get into the shelter already will feel the heat of that sort of news that trans people are not legitimate, and can be excluded or treated as if they’re not trans.

And so that … you know, all of that is very disturbing in terms of the people who will be hit hardest are people who already have the most contact with state power, and who are the poorest and the most vulnerable to, kind of, violent state apparatuses like prisons, police stations, shelters.

DHARNA NOOR: And when the news about that memo came out last week, the Department of Health memo that the Times leaked, a lot of people responded by saying that the Trump administration didn’t have the authority to roll back those protections. Do you think that that’s true, that they don’t have the authority and that they can’t really do anything like this?

DEAN SPADE: Yeah. One thing I want to clarify about the protections thing. So one misunderstanding I think is also happening is I think because trans people kind of mainstreamed during the Obama administration–like suddenly there was a lot of, we were on the TV a lot, and we’re on the, you see us more than you used to–a lot of people think things got better for us and that we were suddenly protected by laws and policies from Obama. For the most part not much changed for trans people. There were a few things the Obama administration began to work on changing, but most of them haven’t landed in trans people’s lives. Trans women are still living in men’s prisons all across the country. That, I think, is just an example of what has not changed.

So it’s not really, to me, just this sort of rollback on protections idea. It’s also the implementation of a new kind of administrative danger of this new federal definition. So I think I just want to sort of help us think about that carefully.

The question of whether or not Trump has the legal authority to do this I think is a complex one. I think–you know, sometimes when you interview lawyers we have a tendency to say things like they can’t do this because it’s against the law. That is a good argument make in front of a court. But in reality if we look at the Trump administration we’ll see that it’s actually pretty lawless, and we need to think politically about this administration in that way. So we can see that, for example, as soon as Trump went into office, even before he’d changed anything in the immigration system, already immigration attorneys were reporting that immigration judges were finding against immigrants way more often than they used to. That the system became emboldened, the police became emboldened. That we can see that it’s not just about what courts say.

Additionally, in terms of questions like can administrative agencies make a definition of gender that is drastically different and is retrograde–actually, administrative agencies have very wide berth by the courts. And as you know, the court system of the United States is dominated by white, straight people, right. I think something like 60 percent of judges are white men in the United States. And even though women of color are a fifth of the population, they’re only 8 percent of state judges. And there’s only three trans judges in the country. So if we really think about the likelihood–like, I’m not hanging my hat on the hopes that we can knock this down in court.

And one of the reasons that matters to me–of course we should do that fight. And you know, people will do that fight in court. But I think that one of the things this can turn our attention to is how can we immediately support trans people in our communities locally instead of waiting for courts to figure this out, hoping something good comes down which I’m not going to hold my breath on. Nor am I going hold my breath that the Trump administration will follow the law, because they don’t in so many other areas. I’m thinking, how can people right now get connected to being a pen pal to a trans person in prison, which can drastically reduce the harm that person is facing? How can people right now help figure out whether or not the domestic violence shelters in their own city let trans women in as women? How can people right now be creating informal housing networks for trans people coming out of prison, or aging out of foster care?

I think that we can get demobilized when we assume that the courts will sort this out for us. And actually we need to be mobilizing community support for trans people under these conditions.

DHARNA NOOR: I think some people would hear you say that, though, and think, oh, with all of this, with all these attacks coming from the federal administration, there’s so much less possibility to act at the local level. Is that true? Or are people finding that there’s more they can do at the local level than the federal government might assume?

DEAN SPADE: In my opinion there’s much more we can do at the local level than the federal government, right. I mean, of course, right now the federal government is a no-go for most of the things people were even trying to get through under Obama. Not that that was easy, or that all of that was going anywhere quickly. Oftentimes even the Obama administration would just make changes that were more surface changes to make them look progressive rather than actually changes that drastically change the lives of poor people, or imprisoned people, et cetera.

So my thing is the local level is really where it’s at, both in terms of–for trans people, local policy has always been vital, making sure, you know, changing policies the level of the DMV, or changing policies level of the local shelter is life and death for trans people. And being in contact with trans people who are in the detention centers, prisons and jails in our cities and states, is vital, because they are essentially disappeared, right. Often they have no family ties. Often no one is watching what happens to them there.

So to me we can actually affect the most change–and, I think, for me, when people are connected to work that really helps people survive right now they also tend to be more mobilized around politics in an active way; not just a passive way of waiting for courts to do something, or occasionally posting something on social media, but actually taking part in their cities and states to figure out who’s being harmed, and how that can change.

DHARNA NOOR: And this–I mean, all of these attacks come amidst a number of other ones from the Trump administration. I mean, they have threatened to ban transgender people from the military service, which many were outraged about. They’ve rescinded guidance to public schools for recommending that trans students should be allowed to use bathrooms of their choice. In May they also said they’d be making changes to their protections for incarcerated transgender people. Are all of these proposals just proposals? Or have any of these had any real effects?

DEAN SPADE: I think a key thing to just say–I want to just speak to the piece around trans people who are imprisoned right now. So I, just again, I think a lot of people, especially because of the existence of TV representations of trans women in women’s prisons, believe that right now trans women are put in women’s prisons, and they are not, with a very, very, very, rare exception. So that–to the extent that Trump is rolling things back it matters, because the existence of those attempts at policy change are, are hopefully part of this step on the way.

But what really tends to change things is people actually being heavily involved. So to me it’s like, if you can get trans women to stop being put in the men’s jail in your city through local activism with your city council, with their county council, if you can change it on that level, you’re much more likely to win something. Right now it’s hard to win this stuff in the Trump administration. So yes, they are rolling out- they a very clear anti-trans agenda. And one thing we can do is try to protect our localities from copying it by making sure that we’re actually pushing for what we want in our localities.

DHARNA NOOR: Do you have any examples that you want to lift up of those sorts of local community efforts?

DEAN SPADE: Absolutely. I think there are a lot of good examples of this. One that is probably one of the most established is the organization Black and Pink. It is a national organization that has chapters all over that connects LGBT people who are incarcerated to pen pals on the outside, which can be a vital, vital thing for having people both–you know, so people inside the prison know that they have somebody on the outside; it makes them less likely to be as extremely targeted. And also it can mean establishing a relationship so that when the person gets out they know people, or have anyone who can do basic research for them on how to find housing, or how to get a job, or any pieces of that. And it can really be also, you know, suicide prevention. It can be a lot of–it’s really life and death to make sure that trans people who are locked up are not isolated from communities on the outside.

So that’s an example that anyone can do right now. Anyone can look at the Black and Pink website and find a pen pal, and that is–you know, and write a letter once a month. That is so deeply meaningful and direct work. I’m also really inspired by a lot of work that’s being often led by queer and trans people and affects trans people but is it broadly for people, for example, in the detention centers. Like where I live in in Seattle there’s a nearby very large detention center in Tacoma, and there is a very enormous movement to be outside the detention center to connect with families, to support hunger strikers inside the detention center, to get complaints out of the detention center about what’s really happening there. It’s privately owned by Jiya corporation and it is exploiting everyone in there, and not providing adequate food and medical care.

So that kind of work has a big effect on trans people, because we are people who are in that system, and also has trans and queer leadership, but isn’t only trans work. So I think there’s a lot of ways into this. One final example I’ll give that I was really moved by is the work in Baltimore, actually, where you are; the jail support project that came out of the Freddie Gray Uprising, where people began to wait outside the Baltimore jail, and just who ever walked out they offer them, you know, rides, clothes, information about benefits; just a few basic things.

And to me that kind of work, when we’re–given the kinds of attacks the Trump administration and more broadly the right in civil society are bringing down on the lives of people of color, queer people, people with disabilities, to figure out how we can create a people’s infrastructure where we actually support each other and where we do it really unconditionally–like, we’re here outside the jail; we don’t care what you were charged with, we don’t care anything except for that you deserve access to some very basic help that will hopefully help you not get arrested as soon as you walk out of the jail again, or not be targeted again by the police.

And so to me, I’m interested in trans versions of that kind of mutual aid, and trans participation in those mutual aid projects. And people are doing accompaniment programs. In Tennessee I met people who were doing, accompanying trans people to medical appointments so that you don’t have to go alone if you’re facing discrimination at the doctor. There’s so many ways people are just trying to actually help each other out instead of only waiting for the government to get better.

DHARNA NOOR: OK. Again, Dean Spade of Seattle University School of Law, founder of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project. Thank you so much for being on today, and thanks so much for your insight.

DEAN SPADE: Thanks for having me.

DHARNA NOOR: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network.