James Henry PT 3: Politicians demand debt reduction but the media rarely connects billions of unpaid taxes on offshore accounts to the issue

Story Transcript

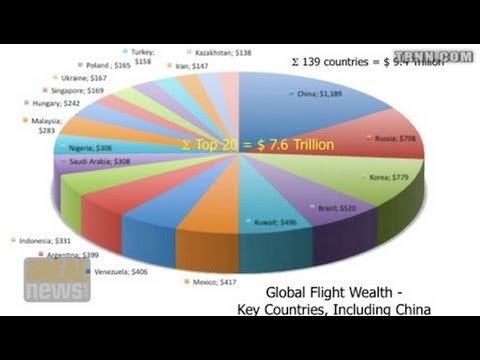

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And we’re continuing our series of interviews about offshore tax havens, $20-$30 trillion at least involved in money that’s being hidden from various governments around the world so that they cannot be taxed. And, of course, the biggest banks of the world are helping engineer all of this. And all of these biggest banks, one way or the other, do business in the United States and in theory should be touched by American regulation. So where is the regulation? And is there any transparency for all of this?

Now joining us to talk about possible public policy solutions to this is James Henry. He’s an economist, attorney, investigative journalist. James served as chief economist at the international consultancy firm McKinsey & Company. He’s on the global board of the Tax Justice Network, and he was the lead researcher of the recently released report The Price of Offshore Revisited. Thanks for joining us again, James.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

JAMES S. HENRY, ECONOMIST, LAWYER, AND INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALIST: You’re quite welcome.

HENRY: So I guess the demand is there needs to be transparency. And you’d think it’d be kind of obvious that the governments of Europe and North America could, if they had any motivation, make these banks disclose all of this. Is anything happening on that front?

HENRY: You know, you have the OECD talking about these issues for more than a decade. Since 1995, they started tackling so-called offshore havens. But their approach to the problem was to single out little islands like, you know, Vanuatu and Nauru in the South Pacific and the Seychelles, Mauritius. You know, there’s a laundry list of about 80 of these little island players. And at the end of the day, very little was accomplished with all of that blacklisting. This industry has not gone away; it’s just shifted to other places.

The orchestrators of this, the systems operators, if you will, are the big banks that we described before, the largest players in the world. And they are, you know, sort of—they don’t really care whether one particular haven lives or dies; they’ll just move on to the next one.

So this requires collective action. We just haven’t been able to get the political will together to have that, because, you know, at the end of the day, many of the countries involved in this are First World countries like the United States, the U.K., Switzerland, that have a big stake in the game continuing on as it has.

So one of the things you see in the pattern of prosecutions, even when you have a big serial violator like a Citibank or a HSBC—. HSBC was recently handed a $1Âbillion fine by the Department of Justice, three weeks ago, for laundering $14Âbillion of cartel money. But, you know, HSBC is a huge institution and it has $20Âbillion of profits last year, so that’s like a parking ticket.

What you don’t see is the Justice Department willing to go in and shut one of these institutions down like they did with BCCI back in the 1990s. BCCI was a Pakistani bank that was involved in all kinds of chicanery and money laundering and arms dealing. But, you know, so is HSBC. I mean, they were facilitating trade with Iran, they were facilitating the Colombian cartel laundering money, and they were telling their compliance officers to back off. So this is an organized conspiracy. It went right to the top. And yet you have—the current chairman of HSBC is a guy named Stephen Green. He’s actually a reverend in the Anglican church. He is the current sitting U.K. trade minister in the U.K. in David Cameron’s Conservative government. This guy is the chairman for ten years of this criminal enterprise. So there’s very little will power on the part of the U.S. Treasury or the authorities in the U.K. so far to crack down on HSBC.

That’s just one example. There are numerous others of where these large institutions have been able to have virtual impunity for, you know, not only their role in the financial crisis and their Libor rate rigging and their—.

JAY: Yeah. What do you make of the media coverage of all of this? I mean, you’ve got the media constantly talking about the crisis, the debt crisis, both in the United States—they talk about the European debt crisis and the—you know, we get practically apocalyptic in the language. But you never hear discussion about, well, if there’s such debt, how about going after all this offshore money. I see almost no mainstream media coverage of the issue.

HENRY: Well, it’s abysmal. I mean, I’ve been writing about this topic basically since the early ’80s, and I’ve had a chance to look at the media coverage in detail. You have—a lot of journalists don’t know anything about the subject and are moving from one story to another, so you’re getting—you know, like this week, I had two minutes on CNN to explain this topic, and half of it was devoted to the response that they had to get from the conservatives, none of whom had—I would describe them not as conservatives but as reactionaries, none of whom had read my paper or had, you know, bothered—they just had the kind of knee jerks as response. But there’s this notion of fair and balanced that they had to dig in.

The second bias that, you know, sort of novice journalists have is that they tend to target the public sector. It’s easy to rail against government. But, you know, we tend to forget that this latest financial crisis was not really made in Washington; it was made by this lobby, by this very influential bunch of banks around the world that pioneered securitization. And, you know, I knew them very well at McKinsey when we were there. They were—we started talking about securitization as a strategy banks ought to have, and it proliferated from the 1980s on throughout the industry to the point where they were securitizing student loans and real estate and car and cars and everything else and selling securities to people that they didn’t understand.

So what happened over time was that this banking industry basically had its way with the regulators in Washington as a result of the vast amount of influence they were wielding and the money they were flashing around. So, you know, this is not an uncaused cause. And it’s not the public sector in the European case or in the United States that was responsible for the origination of this economic downturn which then led to financial crisis in the public sector because of all the collapse of tax revenue and the continuing spending that had to be done just to keep hospitals and schools and roads, you know [crosstalk]

JAY: Right. So if you have a situation where, you know, some people have described this as sort of parasitical capital, but if you have a situation where they deliberately and fraudulently manipulate global interest rates, they deliberately help the super rich avoid tax—and add to that an enormous amount of manipulation going on on the price of commodities, both in terms of hoarding and creating psychological bubbles for shortages and such, to raise prices—and then taking advantage of the low price of commodities in order to increase concentration of ownership, but you have this little financial elite with so much political power that they don’t get regulated, so what do we do?

HENRY: Well, you know, I’d like to describe this first of all as a market-based solution. I have—my very good friend Professor Kotlikoff, who’s at BU, is a lifelong Republican. No one I’ve ever heard gets more agitated and upset about the behavior of these big financial institutions than he does. And, you know, we’ve lately decided to—collaborated on an article where we talk about supporting Sandy Weill’s latest proposal.

Sandy Weill was the chairman of Citibank in 1990s and helped to get the Glass–Steagall Act repealed by working his way in Washington. That allowed these big mergers of financial institutions and allowed investment banking and retail banking to come together. Sandy Weill called for reinstituting Glass–Steagall, which would basically require us to break up these investment banks that have merged which retail banks.

And so, you know, this notion of actually breaking up the big banks as a step beyond regulation is one that I think—you know, Kotlikoff and I are now working on an article that would argue for breaking these banks up, not only on a basis of needing to bring back Glass–Steagall and to stop the speculation, but also that, you know, we’ve had an enormous amount of criminal behavior here. This is—from one standpoint, these institutions are, you know, too big to be honest, and they’re kind of beyond the reach of any particular country’s jurisdiction. Even the United States has trouble doing anything but reaching a deferred prosecution agreement with HSBC or UBS. They just seem reluctant to break them up.

JAY: But is part of the problem here that the elites in the different countries, too many of them are on this gravy train, and that’s where the political power is?

HENRY: Yeah, well, who do you think has these offshore assets with these banks? I mean, who do you think is being lobbied every day by these institutions which have enormous inside access? And who is, in the case of the U.K. we described before, serving as the minister of trade but the chairman of HSBC? There’s a revolving door here that goes on within the elite. So it’s kind of a club that we need to break up.

And I don’t think that’s a—you know, I consider myself an independent, not a Democrat or a liberal. I’d like to see capitalism healthy and wealthy and have all of us being able to participate in that if we can achieve that. But in this situation it seems like a tiny few have been able to get a lockhold not only on the wealth, but also on the political influence.

JAY: Well, we’ll see if—perhaps that horse left the barn a long time ago. I’m not sure you can put it back in again. But I wish you well. Thanks very much for joining us.

HENRY: Thank you.

JAY: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network.

End

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for The Real News Network are typed from a recording of the program. TRNN cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.