Cities around the country, from Baltimore to Oakland, are taking legal action against the banks

responsible for suppressing the London interbank offered rate, Libor. And some 75% of major cities

involved in libor-tied interest-rate swaps stand to reclaim taxpayer losses in addition to libor-backed

mortgage holders who lost money on the rate’s manipulation.

Story Transcript

GIMBEL: I’m here at the Department of Justice in Washington, DC, where a criminal investigation into the interest-rate-fixing scandal that has rocked the financial industry is currently underway. It’s one of many lawsuits aimed at the 16 banks responsible for setting the London Interbank Offered Rate, or Libor, to which hundreds of trillions of dollars in loans, and even more in derivatives, tie their interest rates.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

In the UK, Barclays bank was fined $450 million after an investigation by the Financial Services Authority found that its bankers had submitted false estimates to the British Banking Association of the interest rates at which it borrowed from other banks. It did so, presumably in concert with other major banks, in order to inflate the profits of the bank’s derivatives traders.

The British Banking Association is the non-governmental trade association responsible for setting Libor each day. And its members began rushing to the aid of investigators before the public was made aware of the investigation, seeking to cooperate, in exchange for immunity and prosecutorial leniency.

The Swiss banking giant UBS has already reached a conditional immunity agreement with the DOJ on one branch of the investigation. The fine Barclays paid out to regulators was part of its partial immunity deal reached with criminal investigators in the US and UK. And documents made public by Canadian regulators suggest that Citibank has also sought to provide information on the rate-fixing to lighten its own share of the criminal burden.

Still all 16 of the banks involved in setting libor remain under federal investigation in the US and abroad. And all are targets in a class action suit brought by the City of Baltimore.

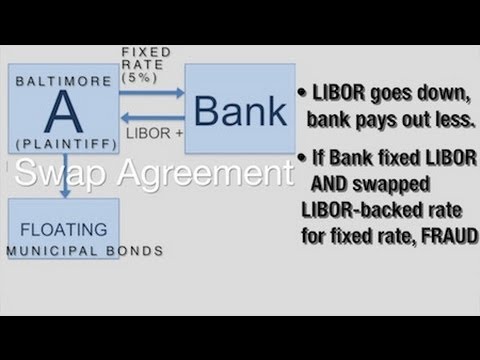

The plaintiffs allege that the conspiracy to suppress the libor rate lowered the value of libor-backed derivatives on their books, exacerbating the effects of the financial crisis of 2008 and forcing deep budget cuts across the public-sector. And a growing group of state attorneys general are putting together a similar class action suit of their own.

To shed light on the details of the case, and its broader implications, the Real News spoke with professor of law and economics, and white-collar criminologist Bill Black.

As Black explains, now that evidence has emerged that there was a conspiracy to rig libor, the case against the banks can be brought outside of financial regulatory bodies and into civil and even criminal courtrooms for violations of federal anti-trust statutes.

BLACK: In terms of anti-trust, this is really a cartel that’s setting price. Supposedly it wan’t setting price, it was simply reporting: this is what we were borrowing at. And what’s come out in the investigation is that wasn’t true. What they were reporting was NOT what was happening, instead they chose to report prices that didn’t reflect reality, but which would help the banks, and in some cases would simply help other people who the banks chose to favor.

There’s one infamous email about helping another trader at a rival firm. It didn’t even look like the banker knew that person very well, and they were happy to help make the rate for them. So a complete lack of integrity. If you have a cartel and it fixes price, particularly if it manipulates price for the benefit of the cartel, tat should be a per se violation of the anti-trust laws. That means you don’t have to establish bad or good, just that it’s a harmful conspiracy against the public. So then it’s a question of were we hurt by it, and if so how much, and what were the damages.

Similarly, lots of people were hurt in their capacity as homeowners, as they borrowed a variable-rate mortgage that was tied to libor. Well, they manipulated Libor up, and there were many many instances that they manipulated it up, you could get locked into a contract for 30 years of paying an excessive interest rate. So that’s not this suit, but that’s the broader kind of suit that the American people – not just Americans – it’s going to be in the tens of millions of homeowners that are affected by this.

GIMBEL: And the amount of money these suits could cost banks could dwarf the $450 million settlement reached between British regulators and Barclays.

BLACK: Everybody that’s in a bad position as a result of the manipulation of libor has a claim that there was fraud in the inducement of the contract. And if it’s fraud in the inducement of the contract, if the bank that sold the swap was one of the entities that was also manipulating libor – and there’s a significant chance that’s true, although it’s a harder factual case, and it will require more investigation – but if that’s true, then the normal rule is I get to void that contract if I wish, and that means everybody gets out of that contract when its bad for you on the other side of the bank’s side of the deal.

And then we’ll see whether they really offset everything the way your source was telling you, and it’s an all-wash from the standpoint of the bank. Somebody is going to end up losing in any event, and those other somebodies are critical to the banks’ ability to create these swaps. So whether or not it’s the bank that suffers the loss, or simply someone facilitating the bank, it can have the effect of saying, whoa, this is a sucker’s bet now for the people perpetrating the frauds, because the other side gets to get out of the deal when it’s beneficial to the other side – the cities, municipalities, states, union pension funds – all these other entities have claims on this Libor fraud because an enormous number of them were in libor-related investments where they lost if they were investors in these circumstances.

And this fear that you could get out of the contract if it proved non-enforceable has always been the terrible fear of derivatives markets. Let’s say the bank has laid it off on some other party as your source was telling you – well that person now also has a claim against the bank, saying, “wait a minute, it’s your initial fraud that started this chain where I suffered the loss – why should I suffer the loss? I was completely innocent, you’re not! In fact, you’re twice bad! Once for rigging the number, and second for fraudulently inducing a client to take a swap on that artificially-reduced number.â€

And therefore those entities have claims against the banks because these deals were overwhelmingly issued by a very tiny number of the largest banks in the world, most of them sitting in NYC. This is something that has potential existential risk to a number of the largest banks in the world.

GIMBEL: But whether or not the hundreds of municipalities and government agencies that lost money from libor-fixing will reclaim taxpayer losses remains unclear. Given the frequent conflicts of interest between elected officials and financial institutions, it may well take popular action to force investigators to reclaim public losses as political scientist Tom Ferguson explains.

FERGUSON: It’s troublesome when you look at things like the association of democratic attorneys general and the association of republican attorneys general. These are effectively 527 political organizations. As far as I can tell, they’re almost never discussed or written about, but what they do is, businesses with an interest give cash to these things then the money goes into attorney generals’ campaigns. And this is the back-door cash, but then there’s the front-door cash. State treasurers and others have to run for office.

There’s no question, every time you look at their campaign finance, you see folks doing business with states. And when you see big behavioral differences between the private sector folks that take these things and try and get their losses repaid, and make the banks buy back these bad deals, this doesn’t happen in the public sector. I think we have a real problem here, a classic money in politics one, undoubtedly different in each state, but if there’s a generalization that can be made, it’s that if you look at money in politics at the level of state politics, most rules on this are really pretty weak.

GIMBEL: Meanwhile the class action suit filed by the city of Baltimore progresses, and across the country the Oakland City Council has dmanded the immediate termination of its swap agreement with Goldman Sachs. More and more people look into their cities’ finances and take matters into their own hands as their schools face closure, public services continue to face deep cuts and they are asked to bear an increasing share of the costs of financial crime.

Put as the general public slowly begins to discover the scale of the fraud they’ve been asked to pay for, regulators at the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England knew that manipulation was going on at least as early as 2008. In the next part of our series, we’ll look into what they knew, when they knew it, and why they didn’t do more to stop the banks’ criminal conspiracy.

For the Real News, I’m Noah Gimbel in Washington.