Investigative journalist Chris Hamby on coal miners quest for justice buried by law, medicine, and industry

Story Transcript

JAISAL NOOR, TRNN PRODUCER: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Jaisal Noor in Baltimore.

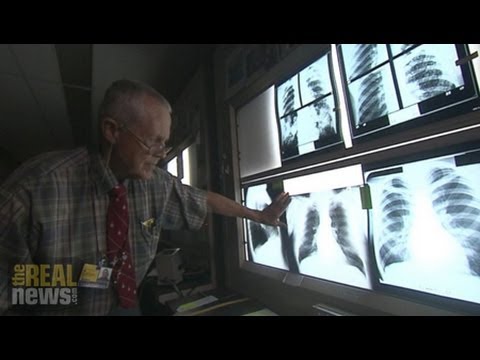

We are continuing our discussion with Chris Hamby. He’s with the Center for Public Integrity. Along with ABC News, they just recently released a report called Breathless and Burdened: Dying from Black Lung, Buried by Law and Medicine.

Thank you so much for joining us, Chris.

CHRIS HAMBY, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER: Thanks for having me.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

NOOR: So, Chris, we just talked about your exposé on Johns Hopkins. But I want to kind of broaden this discussion. And I want to start by asking you what drew you to this story, drew you to the plight of the Appalachian coal miner and the problems of black lung that’s devastating the lives of so many coal miners in America today.

HAMBY: It really for me started a couple of years ago with a report that came out about the upper big branch disaster in southern West Virginia that killed 29 miners. And they had–it was a–sort of a small find within this larger report was that of the 29 miners, 24 had enough lung tissue that they could do an autopsy, and of those 24, 17 had signs of black lung. And that was even including younger guys and guys who had worked that long in the mines. Now, that was pretty shocking, and I, like most people, or like many people, probably, thought that black lung just probably wasn’t that much of a problem these days and didn’t realize the extent to which it is still around. And when I started to look into it more, it turns out it’s not only still around, but actually since the 1990s there’s been a resurgence of the disease.

Since 1969, when standards were passed to limit the amount of coal dust in the mines, the disease prevalence rate has steadily declined. That was until the late 1990s, when the government began documenting a resurgence in the disease and a particularly disturbing trend of younger miners getting more severe forms of the disease that are fast progressing.

And so then the last year I did a story about that with NPR and focused on the resurgence of the disease. And as I was doing that story, then sort of started hearing all these complaints about the benefit system and miners saying they’d essentially given up because they felt like there was no point in even trying, that they were just going to be overwhelmed by the coal company–. And the awards rate is very low. It’s about 14percent right now, and that’s higher than it has been in recent years, and that’s at the initial level before the coal companies even appeal, and most awards they end up appealing. So the odds of a miner winning benefits and keeping them are not great.

NOOR: And you spent over a year just on this investigation alone. Can you talk about some of the coal miners you’ve met and what black lung and going against these coal companies, how it’s impacted their lives?

HAMBY: Right. It’s the one thing that will stick with me more than anything from this project is time in these men’s living room and in their kitchens. They invited me into their lives. And sitting there watching them breathe through–needing oxygen or gasping for breath–we’re talking about men in their 40s who can hardly breathe, they could hardly get up and walk to the kitchen–it’s hard to see that and to know that it’s unnecessary for that to be happening. And for these men it was really–it was almost an insult to injury or a slap in the face, the benefit system, I mean, because they felt like they are not naive. They don’t think that “I’ll go into a coal mine and everything will be fine.” They realize that is a dangerous job, that there is the possibility that they could be killed in an accident or that they could get lung disease.

But it’s almost–the way almost everyone described it to me was almost like a contract. They felt like the agreement, what they signed up for was that they would risk their lives and their health, and in return they would get a fair day’s pay, and if anything happened to them that the benefits system would be there for them. And what they found a lot of times in their later years, now that their bodies are used up and they’re sick, is that it’s not there for them.

NOOR: And so I wanted to ask you–in the first part of our conversation, we talked about the role Johns Hopkins played in often finding that the coal miners didn’t have black lung and therefore are not eligible for benefits. But can you briefly talk about some of the other efforts the coal industry’s used to defeat these black lung claims?

HAMBY: Right. A good example, for instance, the first installment in the series, focused on probably the most prominent law firm that does federal black lung defense. Iit’s a law firm named Jackson Kelly based in West Virginia. But they have offices throughout Appalachia and in Denver, DC. They are national in scope and they’re probably one of the biggest, if not the biggest black lung defense firms. And as the investigation showed, they have a record going back years withholding evidence from miners that actually showed that they had black lung.

Now, their defense is that they’re not doing anything wrong by doing this. That remains to be decided. And this is something that has played out over many years.

But what has happened is that occasionally because of this sort of game-changing evidence that was never turned over, miners have lost claims. In one case, the one that I focused on the first story, the miner actually lost his claim because of key withheld evidence, had to go back to work for a number of years. And by the time he finally retired, he was essentially almost dead. He needed a lung transplant, and he died waiting on that lung transplant. And it was only shortly before then when they discovered what had been withheld from him. And that, the fight over his case, is ongoing now.

NOOR: Chris Hamby, thank you so much for joining us.

HAMBY: Thanks for having me.

NOOR: You can follow us @TheRealNews, and you can Tweet me questions or comments or some story ideas @JaisalNoor. Thank you so much for joining us.

End

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for The Real News Network are typed from a recording of the program. TRNN cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.