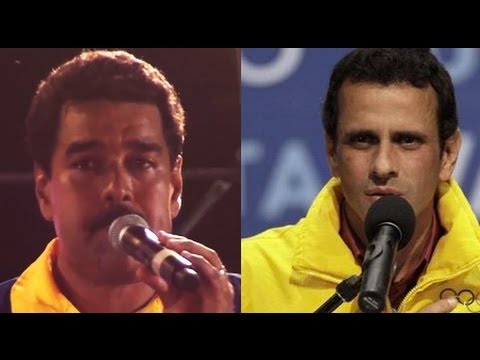

Miguel Tinker Salas: The Presidential elections in Venezuela will decide if the socialist transformation will continue or a pro-US elite will return to power

Story Transcript

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore.

[snip] the elections in Venezuela [snip] April14 to decide who is going to become the new president following the death of Hugo Chavez.

Now joining us to talk about some of these developments is Miguel Tinker Salas. He’s a professor of Latin American history at Pomona College in California. He’s published and lectured widely on Venezuelan politics. And he is from Venezuela. He’s author of the book Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture, and Society in Venezuela and a soon to be released book, Venezuela: What Everyone Needs to Know.

Thanks for joining us again, Miguel.

MIGUEL TINKER SALAS, PROF. LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY, POMONA COLLEGE: Thank you very much.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

JAY: So we’re going to get into kind of the two different visions for Venezuela in a minute. But before we do, let’s start with the main–one of the main accusations, you could say, of the opposition against Maduro and the Venezuelan party he leads is that they’re using a lot of resources of the state to reelect Maduro. They’re saying military officers that are supposed to be neutral are coming out in support of Maduro. They’re talking about him having, you know, unequal access to state-owned media. Anyway, what do you make of that, that this isn’t very equal in terms of how the state gets used?

TINKER SALAS: I’m not quite sure I accept the argument. First of all, the idea that Capriles Radonski somehow doesn’t have the same kind of presence in Venezuela, I think, is an error. The reality is that he has the presence in Venezuela. He’s been a candidate for the opposition in the October election against Chavez, in which Chavez defeated him by close to 11 different points. He has been part of the Venezuelan political scene since the 1980s. He has access to all the private channels in Venezuela. He has access to all the social networks in Venezuela. He has access to the international media, which has been running very, very favorable articles about him in Venezuela, and abroad as well, which always get replayed in Venezuela.

Undoubtedly, the incumbent in this case, Maduro, because he has the benefit of being in the presidency for the time being, enjoys a certain amount of benefit from that. But the idea is that the media is still primarily controlled by the private sector in Venezuela. The government-controlled media, the TV channels and radio channels, are actually a very small portion–less than 20percent–of the actual media in Venezuela. So if we look at the print media, the digital media, the television media, most of it is in private hands and most of it has been very supportive of Capriles Radonski. He has a presence in Venezuela. He has a voice in Venezuela. And he’s there ever-present, as well as internationally.

JAY: So let’s get into more the substance of the difference between the two leaders. Capriles, the opposition leader, has been talking more like a sort of social democrat and essentially talking about a sort of Chavez program and sort of having a social safety net, but only executed more efficiently. I mean, to what extent do these two leaders represent two different visions for Venezuela?

TINKER SALAS: I think we have two different visions, two different programs, and two visions of the nation, because if one has to go beyond the rhetoric that Capriles is using to try to get elected, if you go back to the October election that Chavez defeated Capriles, the MUD, the M-U-D, the national unity table for the opposition actually had a very long set of principles that included discussions that sounded very much like a neoliberal program, talking about privatizing the oil company, talking about reversing the course of the international policies adopted by Venezuela, talked about recasting Venezuela’s role in the region, realigning itself with the U.S. in ways that had been done in the past.

And I think that overall what we see coming out of the opposition is still very much that. They want to return Venezuela to what they imagine Venezuela was before 1998–a faithful ally of the U.S., a country that was an oil-producing country whose oil enterprise, PDVSA, was a leading multinational. And they were on their way to privatizing the oil company. So I think that that largely is still the vision that drives–. And the other part of that is the return to the privileges enjoyed by a middle class and an elite sector of society that was willing to sustain 60percent of the population living in poverty, inequality, high crime rate.

And I think the other vision, somewhat eclectic and somewhat still undeveloped in the discussion of 21st-century socialism, has attempted to take and recast the nation, recast its past, its present, and its future, realign it with Latin America to establish it as a regional leader. Many of the promotion of the issues of regional integration that Venezuela took up in the 1990s, late 1990s, and 2000s are today a reality, the vision of the country that’s different, that actually heightens it or relates it to its Afro-Latino heritage, its indigenous heritage, recognizing its indigenous past, recognizing its role as a Latin American country addressing inequality, taking the national oil company and actually using its profits for social investment, upwards of a 60percent increase in social investment to reduce poverty, inequality, to have social movements, to have social councils, to have community organizations. It’s a whole different vision of the country, and I think there are two visions, two models, and two interpretations of what the future of Venezuela should be like.

JAY: So if you read or watch American media, I don’t know that the name Chavez ever got mentioned, including after his death, without the word dictator in front of it. And they would kind of explain that the fact that he would win election after election and still call him a dictator was that these oil profits get used in order to sort of gain votes amongst the poor, and so they vote for him, but it doesn’t mean that he isn’t still acting like a dictator once he’s voted in. I mean, that’s sort of the predominant narrative in American media. What do you make of it?

TINKER SALAS: I think if you were to rely on the U.S. media to understand Venezuela or even Latin America, you would really not have the basis with which to understand it. It would seem like this quandary to you, because how do you explain a country that was one of the number-one U.S. allies in the region, a model democracy which the U.S. promoted, its ally in the UN and the OAS, and then you simply say, well, Chavez shifted it all?

No, I don’t think Chavez shifted it all. There was a glaring inequality in Venezuela that was heightened by the fact that it was an oil-producing country, and it had the resources with which to address the question of inequality, then chose not to. And that’s the reality of why Chavez came to power, and the fact that it was fueled by the existence of social movements. It wasn’t simply two parties that knew how to transition democracy and how to efficiently run a society. It was not that. That was not the reality.

And much of what we read in the media, then, doesn’t really give us the insight, because you’re right: they say, well, he reduced poverty, but he was a dictator. He reduced poverty, but he was an anti-U.S. element. He helped regional integration and promote regional integration, but the reality is that many of the countries in the region now chart their own course. It’s always from the framework of what is in the interest of the U.S. and not what’s in the interest of the Latin American countries.

JAY: What do you make of the report that comes from Human Rights Watch? I mean, Human Rights Watch has been very critical of U.S. policy in Afghanistan, in Iraq, and other places in the world. When it comes to Venezuela, Human Rights Watch has been part of this, you know, you could say chorus declaring Chavez essentially a dictator. I’m not sure if Human Rights Watch uses exactly the word dictator, but they talk about, you know, grave violations of human rights. They point to the jailing of this Supreme Court judge particularly and the closing of a TV station. And they seem to time their reports, I have to say, to be very connected to when there’s elections. It seems to me if you’re going to do a Human Rights Watch report like that, it shouldn’t come out just weeks before an election. That seems to be the pattern. But set that aside. What do you make of their, you know, very harsh critique on the human rights side?

TINKER SALAS: I think it really in some ways exposes their hand, because if you look at what they’re saying in Venezuela, as you say, it seems to be very political-oriented. And many of their reports rely primarily on opposition sources. They have not done the groundwork, research to prove that these arguments exist. They put together a context, but then they don’t explain the situation in which it developed.

Yes, there was a judge arrested, but that judge was also involved in releasing a person that had been arrested for corruption and fraud, so that there’s really not a context in which to understand these so-called human rights violations.

And they speak of the need for separations of powers as if that was something that had existed previously. I think we all would like to see a separation of powers, the independence of these different powers–the judiciary, the presidency, the congress. But the reality is much more complex in Venezuela. And it’s the same thing when it relates to other countries in Latin America. Why wait in Mexico, for example, to come out with Human Rights Watch report at the end of the Calderon administration when we knew all along that these issues were happening, so that one needs to–one always questions the political timing of many of these reports when what they’re talking about has been known for quite some time?

JAY: Alright. We’re going to be asking a representative from Human Rights Watch to see if they’ll come on The Real News and talk about this.

Thanks very much for joining us, Miguel.

TINKER SALAS: Thank you very much. Have a good day.

JAY: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network.

End

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for The Real News Network are typed from a recording of the program. TRNN cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.