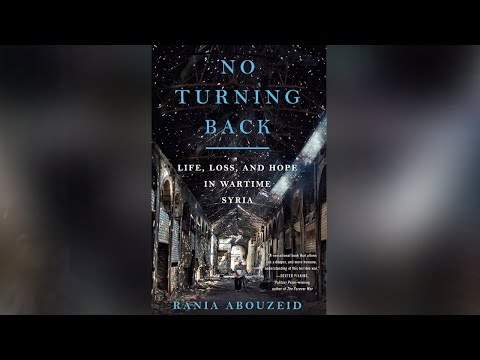

Award-winning journalist Rania Abouzeid discusses her book “No Turning Back: Life, Loss, and Hope in Wartime Syria,” based on years of on-the-ground reporting since the 2011 uprising.

Story Transcript

AARON MATE: It’s The Real News, I’m Aaron Mate.

We’re here with Rania Abouzeid, she is an award winning reporter who has covered the Syrian crisis from the beginning. She’s the author of No Turning Back: Life, Loss, and Hope in Wartime Syria. So Rania, you were in Syria when the uprising broke out. Take us back to those earliest days of the revolution. What did you witness?

RANIA ABOUZEID: I witnessed people who took to the streets with nothing but their voices. I witnessed people who took to the streets knowing that they might not return. I witnessed reprisal. I remember being in some protests here around the suburbs of Damascus and hearing the gunfire break out and seeing protesters who didn’t even break their step. It was a very heady, very dangerous, very volatile time. And I mean, let’s remember the context as well. It was the so-called – I’m not going to call it Arab Spring because that’s not what the locals call it, but the Arab Uprisings that we’d seen in Egypt and Tunisia, things were happening in Libya and Yemen. So, it was within this broader context of what was happening in the region.

AARON MATE: And at what point does the revolution, from what you observed, shift from this Uprising calling for democratic reforms into the proxy war that it’s become since?

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

Let’s see, the proxy war. Well, in my reporting in No Turning Back, I went back to answer some of these questions. And I realized that actually the Saudis, via Lebanese, got involved pretty early, and the Lebanese, anti-Assad factions got involved in, I’m going to say like, late 2011. And then it wasn’t until early 2012 that the Saudis and the Qataris decided to really step in, in a more organized fashion, to try and arm the uprising. And in my book, I went back and reconstructed those first meetings. I found out who was in the rooms, what each party said, what was promised and what they intended to do. And my reporting indicates that that was around, I’m going to say, March 2012 when that started to happen.

AARON MATE: I believe you were the reporter who broke the story about what you called the Istanbul Room, and how that was used to coordinate the delivery of weapons and support to the armed factions in Syria by Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Can you explain what the Istanbul Room is?

RANIA ABOUZEID: Well, it wasn’t a room, it wasn’t a physical room, it was an idea, and it was headed by a Lebanese politician called Okab Sakr. And the idea was that you had Okab Sakr and about four other Syrians, and that was one layer. And then the layer underneath it was a whole host of middlemen, and these middlemen came from the various Syrian provinces and they were supposed to have the links on the ground to know which groups were actually working and which groups deserved the free arms and ammunition. But it was a shambles. These middlemen were rotated in and out, some of them didn’t have real links to the ground, to groups on the ground. And the supplies that were promised were inconsistent, and they were much less than what was promised.

And I detail in the book the arming of the of the uprising on that side and why every sort of failed from the point of view of the opposition. At the same time, of course, we had fighting alongside Assad’s forces was Lebanese Hezbollah with Iranian advisers. And years later, we saw the Russian Air Force take to the skies of Syria.

AARON MATE: And after the Saudis and the Qataris get involved, you also had the CIA. One of the interesting things I found in your book is that you talk about a movement called the Hazzm movement working with the CIA and informing them of ISIS locations. You report that in one instance, in Latakia, if I have it right, that the CIA was informed of the presence and the exact locations of ISIS commanders, but didn’t do anything with that information.

RANIA ABOUZEID: Yes, and that was something that I learned from many people. This reporting is based on the actual … I mean, I had copies of the actual intelligence files complete with photos, disks all sorts of things. So I had the reports that were handed over to the CIA, and I didn’t speak to just one of these guys who was doing this work, but I spoke to two of them independently and I also had some of his information. And this was very sort of demotivating for the guys on the ground because they were, at huge risk to themselves, going into some of these ISIS houses.

I mean, I remember seeing photos of the routers. I mean, they had the serial numbers of the routers, which there were photo snapped in the homes of these foreign Islamic State emirs, commanders, in and around Latakia province. So you can imagine the danger of getting that. And then nothing sort of happened. And it didn’t happen until after the U.S. and coalition forces decided to engage in a war against Islamic State after starting in Iraq, after the attacks on the Yazidi community there. And then they turned to Syria. But for the Hazzm movement, at least, it was too late because Hazzm was eventually wiped out by Jabhat al-Nusra, which was the al-Qaeda affiliate, not by Islamic State, which had been cleared out of those territories by the time that the coalition forces decided to engage in a war against the Islamic State.

AARON MATE: You also go back in the book and you revisit some of the earlier incidents that you reported on based on new information. And one of those key places is Jisr al-Shughour, if I’m saying that right. So there were said to be a mutiny there of Assad’s soldiers that led to many of them dying, but then you revisited and then found a different story. Can you explain what initially was claimed and then what you found?

RANIA ABOUZEID: Initial claim was that the army had split in Jisr al-Shughour and that there was a mutiny to protect the civilians in the city. But the actual truth is that there was no mutiny, and it was armed civilians who had killed Syrian soldiers and buried them in mass graves. They filmed those graves and they claimed that they were full of victims of the regime, when in actual fact they were regime soldiers. Obviously you can’t justify that, but to give you some about the background, Jisr al-Shughour it was one of the key cities in the 1980s that was punished by Bashar’s predecessor and father, Hafez al-Assad, for an earlier Islamist insurrection.

And the people of Jisr al-Shughour, many of them, the scars was still deep, they still remembered it. And for some of them, at least, they were waiting to take revenge against a regime that had humiliated or killed or kidnapped or done whatever to their fathers and grandfathers. And they took that opportunity in June 2011 when they did this. But it was a cover up at the time that I went back and have now in the book corrected that record for history’s sake and for the sake of the people who were in those mass graves. We have to do that as journalists and we have to correct the record and we have to also not cherry pick information and place it in context whether it’s the Jisr al-Shughour incident or other incidents, for example, by labeling all of Idlib al-Qaida or something like that. It’s simply not fair to the people who live there. It’s more nuanced than that, and we have to be wary of those nuances.

AARON MATE: You follow four characters in the book. Can you give us a brief sketch of who they are and why you decided to tell the story of Syria through these four central people?

RANIA ABOUZEID: There are four main people and there are other people who branch off their stories. And I decided to construct the book this way because, in my experience, it’s the easiest way to help readers understand a complicated place with complicated names, and Syria is a very complicated conflict anyhow. Because if you just remind people that it’s about people, then it becomes easier to sort of understand. I’m not interested in putting people on pedestals or demonizing them, that isn’t my goal. My goal is to try and help you to understand what happened. So there are some characters in the book that are pretty unsavory by anybody’s definition.

And one of those characters is Mohammad, for example, and he is an al-Qaida supporter who becomes an al-Qaeda emir, and he becomes an influential al-Qaeda emir in Idlib province. But you see how he came to be the man that he is. And then you see, through his story, his story partly helps explain the rise of how al-Qaeda exploiting the Syrian uprising to reconstitute itself. There is also the story of a commander who actually started off being a university student, a poet, a literature student in Homs University. His name is Abu Azzam, and he became a commander in the Free Syrian Army. And through his story, you see or you get a better understanding of the Free Syrian Army and what happened to Abu Azzam’s group of battalions over a number of years.

I also tell the story of Ruha. Ruha, when readers first encounter her, is a nine year old girl. And through her story, the story of her aunts and her parents, you see how war can affect a regular family and what it does to everyday life, people who are trying to just get by. And then there’s the story of Suleiman. Suleiman was a very privileged young man. His family had ties to the regime, and he becomes a civil activist. And you see what that decision costs him. And in telling Suleiman’s story, as well, you can see some of the challenges that civil activists faced and why the guys with the guns managed to, in many places, overpower them or quieten them. And there are other characters who branch off these characters.

One of them is – I tell the story of an Alawite family that was kidnapped by Mohammad’s men, actually, by men who Mohammad knew, the al-Qaida fighter in Latakia. Unfortunately, I’ve been banned from entering government held parts of Syria since 2011 for reasons that I don’t know so. But I nonetheless wanted to try and tell some parts of that side of the story and to see what to try and get to the two sides of the front line in Latakia. And that is told through the story of this Alawite family and of Hamas man on the other side.

AARON MATE: How did you find out you were banned by the Syrian government, and if you’re still prevented from going, then is your only way of entering Syria via Turkey?

RANIA ABOUZEID: Yeah I found out, initially, some Syrian activists used to check their names periodically to see if they’re wanted at check points. And one of them contacted me, telling me that they’d come across my name on this list. And shortly after that, human rights organizations, Amnesty International, contacted me to warn me, to tell me that my name was on a leaked list of Syrian activists, even though I’m not even Syrian, I’m Lebanese/Australian. But so, my name was included in their names, so I knew that it was real.

And then I double checked that with some sources within the Assad regime whom I knew, and they also told me that that this is all real. And it’s still holding, and I’m still wanted by three of the four main intelligence agencies. And if anything, it’s just an indication of the fact that you can’t push back, you can’t question, you can ask why. I have no means to challenge this arbitrary decision, I’m not even informed of like why this decision was made. But it helps you to understand something of the system that exists in Syria.

AARON MATE: In terms of looking at the conflict with nuance, I want to ask you about that in the context of this group, the White Helmets, who became very well-known in the West for their rescuing of civilians in buildings bombed by the Russians and the Syrians, received awards here in the West, and were generally regarded as heroes. They have their critics, who accuse them of working with al-Qaeda directly. There have been videos showing that White Helmet members are present at executions carried out by al Qaeda militants. What’s your sense of the truth there about the White Helmets? When they’re accused of taking part in atrocities, are those aberrations from the overall group’s mission, or is there something more complex here?

RANIA ABOUZEID: If anything, it indicates that you can’t report Syria from Twitter, you can’t report it from social media, you can’t report it based on glimpses, you can’t report it based on the “testimony” of people who have never been there, who don’t understand Arabic and who are relying on social media posts. You just simply can’t do that. And I think that Syria is a conflict where it has become so polarized, and information has become so weaponized, that you can just about throw any claim out there with the flimsiest of evidence, if any at all, and somebody will agree to it, somebody will find it believable and it will stick. So, you can’t cover these things by remote control. I’m sorry, you simply can’t, you need to be there. You need to see. You need to see what happened before and after that snippet of video was captured. You need to see so many things. I mean, you just can’t report it by remote control. And It’s too complicated to do that. You have to be there.

AARON MATE: Right, but that can apply to both sides.

RANIA ABOUZEID: I mean, every side. I’m not talking about one side or the other, absolutely not. I’m talking about all sides. You have to be there, you have to see, you have to be as independent as you can. You can’t be – like if you don’t speak the language, you’re going around with government minders who haven’t been to Syria before, and you’re relying on those government minders to tell you, “Okay, you can talk to this person, not to that person,” well then how realistic is the testimony that you’re going to get? As opposed to going in there, talking to whomever you want, being able to navigate these sorts of pressures. And let’s be clear, that they are precious. So it’s a very tricky, very dangerous thing, and it doesn’t help when you have these Twitter arguments between people who have never been to the places that they claim to be experts about.

AARON MATE: Well, I’m one of those people who have taken part in Twitter arguments. I’ve never claimed to be an expert, but I have taken part.

RANIA ABOUZEID: I didn’t know, sorry, I wasn’t –

AARON MATE: No, no. Listen, it’s not a point of pride. And it’s true that it’s very volatile on Twitter. I’m sure that none of us who have been there are speaking from very limited knowledge. On the issue of the White Helmets, though, in terms of what you observed on the ground. I mean, what can you tell?

RANIA ABOUZEID: I’ve only ever seen them pulling people out from under the rubble, to be honest with you. That’s the only thing I’ve ever seen them do.

AARON MATE: Do you plan on going back to Syria in the near future?

RANIA ABOUZEID: I have no idea, I’m just back from Iraq at the moment, and I’m doing a lot of travel to Iraq recently. But I mean, certainly Syria is on my radar, it’s still of great interest, it’s still of great importance. And what happens there, it’s critical, not just for the lives of Syrians, but it has had such an effect beyond its borders, as we all know. I’m certainly not going to look away from Syria.

RANIA ABOUZEID: We’ll leave it there. Rania Abouzeid, award-winning reporter who has covered the Syrian crisis from the beginning. Her book is No Turning Back: Life, Loss, and Hope in Wartime Syria. Rania, thank you.

RANIA ABOUZEID: Thank you.

AARON MATE: And thank you for joining us on The Real News.