Education finance expert Jess Gartner joins TRNN’s Jaisal Noor and Stephen Janis to discuss recent right-wing news coverage of Baltimore city schools

Story Transcript

JAISAL NOOR: This is The Real News. I’m Jaisal Noor in Baltimore.

Last year, Sinclair Broadcasting, a network with close to 200 affiliates that reach almost 40% of American households, made headlines for forcing its anchors to read must-runs that often have a conservative pro-Trump spin; for example, on fake news. Former FCC Chairman Michael Copps said, “Sinclair is the country’s most dangerous broadcaster because it’s weaponizing local news, which polls show Americans trust to be free of spin or bias, for political gain.”

MICHAEL COPPS, FORMER FCC CHAIRMAN: I wish everybody in America could see that viral messages that went out, depicting hundreds of stations that they own all reading from the same script.

JAISAL NOOR: But Sinclair’s right-wing bent isn’t limited to just national news. What’s gotten far less attention, but is also deeply concerning is Sinclair’s venture into local education reporting in Baltimore. Schools here face tremendous challenges— declining enrollment, aging buildings, a lack of adequate funding for facilities and student learning, and violence that too often spills from communities into classrooms. Critics say Sinclair Broadcasting is helping a Republican Governor unfairly malign this majority black school system and rally public opinion against what Baltimore schools badly need: equitable funding to overcome generations of disinvestment and structural racism.

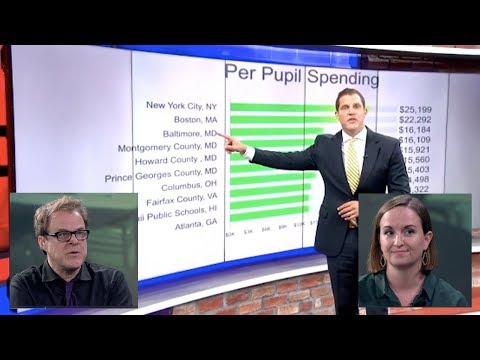

CHRIS PAPST, PROJECT BALTIMORE: This is the list right here released by the US Census for 2019. Of the 100 largest school systems in America, these are the ones that spend the most per student. Now, last year, Baltimore City was number five. But this year, spending $16,184 per student, it has moved up to number three, only behind New York City and Boston.

JAISAL NOOR: Just in time for the beginning of the school year, a new report by Sinclair Broadcasting’s Project Baltimore rehashes the argument that Baltimore schools aren’t getting the results they should with all the money they are getting, especially compared to other Maryland districts.

CHRIS PAPST, PROJECT BALTIMORE: So what are you, the taxpayer, getting for all of this money? Well, Howard and Montgomery Counties are known for having good school systems, but even as City Schools is now the third most funded school system in America, federal data tells us it’s also one of the lowest performing.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

JAISAL NOOR: But critics argue this data is misleading and essentially meaningless when put in the full context. In June, education consultant Jess Gartner tweeted, “Certain Maryland politicians and journalists LOVE to cite a ‘fact’ about how Maryland districts top the list of per-people spending in the country. I’ve repeatedly talked about how these ‘stats’ are not only very falsely represented but are totally meaningless.” Anyone who has been to a Baltimore school, or at least seen images of them on TV, knows that many are falling apart and are underfunded, state commissioned studies say, by at least $250 million a year. And it may give some pause to hear Baltimore, where nine in ten students live in poverty, be compared with Howard and Montgomery Counties, two of the richest districts in the entire nation.

I asked Chris Pabst, author of the story, how he arrived at his methodology of concluding Baltimore is the third best-funded school system in the country. Did he choose to exclude some of the factors like poverty and family income, which are known as the greatest predictors of student test scores, or was he unaware of them? Pabst’s response: “Our story accurately cited federal data collected and distributed by the US Census Bureau and National Assessment of Educational Progress.”

Despite that, and following a pattern we’ve covered on The Real News and in the Baltimore Beat, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan once again cited Sinclair’s deceptive reporting, writing on Facebook, “Baltimore City Schools is now the third highest-funded large school system in America, but sadly, it’s also the third lowest performing. Obviously, providing record funding is not the solution,” he said.

Now joining us to discuss this are two guests. Jess Gartner is an expert in all of this, a former teacher, she’s the CEO and Founder of Allovue, which empowers K through 12 educators to strategically and equitably allocate financial resources, working with school districts across the nation to budget, manage, and evaluate spending. And of course, Stephen Janis, award-winning investigative reporter at The Real News and a former reporter at the local Sinclair affiliate, Fox 45. Thank you both for joining me today.

STEPHEN JANIS: Thanks for having us.

JESS GARTNER: Thanks for having us.

JAISAL NOOR: So Jess, Governor Hogan didn’t respond to our request for an interview or a comment about some of the questions that you and others have raised about this reporting that he’s citing, and these attacks against the Baltimore school system. Chris Pabst says, “Look, I’m just reporting the data, just reporting the facts.” Talk about what you find so misleading about this.

JESS GARTNER: Sure. So the rankings that are continuing to be presented are a list of the top 100 largest school districts in the country. For context, there are over 13,000 school districts in the country, so that list is less than 1% of all school districts. So they’re really extreme outliers of all school districts. It’s not really meant to be representative of the entirety of school spending in the nation. If you took those Maryland districts and plotted them across all school districts, we’re actually very middle of the pack in terms of spending.

And the reason why this is particularly interesting for Maryland school districts is that Maryland, in and of itself, is kind of an outlier in the way that we define what a school district is. Maryland uses our large county systems as our school district jurisdictions. That’s really unique in the country. So we are sort of an outlier among outliers in that we have a large percentage of these very large districts, on a list of large districts. And I think it’s really interesting that one of the districts that’s on this list that is ahead of us in school spending is Boston in Massachusetts, which is actually a state that our legislature has looked to in terms of educational excellence.

So the fact that we have a lot of districts on this list, say a lot more about how we define boundary lines for school districts. And also, per-pupil spending is largely driven by labor, labor costs and wages. So it really says a lot more about the cost of living in those states and the way that we draw lines of school districts, than it says anything about the efficiency or the performance of these school districts.

JAISAL NOOR: And Stephen, you have covered politics and Annapolis, and events around the country and the state for a long time. And you used to work at Sinclair Broadcasting.

STEPHEN JANIS: Yeah.

JAISAL NOOR: What are your thoughts when you hear about how the numbers they present just don’t add up?

STEPHEN JANIS: Well, I mean, it’s been a very common narrative, and it’s a very effective and popular narrative to look at Baltimore and point to it as a failure because it’s very profitable for people, and in some ways politically efficacious, right? Let’s look at it this way, Hogan completely embraces, and I think this is a question that’s going to come up, but Hogan, our governor, embraces the reporting immediately, uncritically and that’s for political gain because it’s easy to say.

One of the overarching narratives of this state that we live in is the failure of Baltimore. And the failure of Baltimore fuels a lot of things. I mean, I don’t see a cost on, let’s say, police spending per resident, right? Or comparing that, the fact that we actually have more police per resident than probably any other jurisdiction. It’s always focused on education because education is an important venue for agency of a community. It’s critically important. It’s a critically important way to subdue a population. So I think this just fits into the overarching narrative that Baltimore must fail on some level. If it’s not failing, it’s not politically expedient for the people who want to work off that and benefit from it.

JAISAL NOOR: And of course the context, which is all unfolding, is that there’s been a commission called the Kirwan Commission that’s been meeting for years now that has determined that the schools need billions of dollars of funding every year. And there was a big election last year, which Hogan won, in part because he said the schools are not underfunded, they’re mismanaged. That was a big rallying cry throughout his campaign, and he’s been continuing this as the school year starts, but I want to go back to this Project Baltimore story because it’s not finished.

STEPHEN JANIS: Sure.

JAISAL NOOR: It ended with a quote from Marta Mossburg, a conservative columnist and Fellow at the Maryland Public Policy Institute, a right-wing libertarian think tank.

MARTA MOSSBURG, MD PUBLIC POLICY INSTITUTE: Money is definitely not the answer. I mean, look at Maryland as a whole over the past 20 years. School spending has gone up something like 45%, and education standards have been raised, more teachers have been hired, staff has been hired, and student scores have just stagnated.

JAISAL NOOR: So Jess, what’s your response to Marta Mossburg?

JESS GARTNER: Sure. A couple of things. For one, to say it’s not about the money is an opinion that flies in the face of an unequivocal body of research by economists and education policy experts around the country. We now have multiple reports verifying that, absolutely, there is a correlation between needs of students, the resources they get at school, and their performance. And a big part of that is that the equity of funding is at the core of that research, that not every student requires the same resources at school. So we can’t just look at levels of funding in terms of absolute value. We have to look at it in the context of the student populations, and the needs and characteristics of those students.

And in Maryland, we have an incredibly diverse population, but we also have a highly segregated population. And we also have extreme concentrations of poverty, of students with special ed, and of other students with very high needs at school. So when we’re looking at funding levels, if we’re not talking about those characteristics, if we’re not talking about student need, and if we’re not talking about equity, then just looking at those dollars is really meaningless. It’s not an apples to apples comparison.

The second argument is, I keep hearing again and again, “Spending is increasing, we’re putting in historic levels of funding.” I mean, that’s just essentially how the economy works. Everything costs more over time, unless we’re in the heart of a very deep recession. I mean, we also have historic housing costs, we have historic costs for a gallon of milk, we have historic costs for higher education, almost every public service. I mean, what you’re looking at is really spending stabilizing as a percentage of GDP growth over time. So this obsession with the levels increasing is really a moot point. It doesn’t say anything about how those dollars are spent, or where they’re going, or what we’re trying to accomplish.

So the conversation needs to be completely reframed to, one, focus on the equity of those dollars, so how are they being distributed based on the needs of students? And two, how much do we need to meet the goals that we want? And a really simple analogy that I love to use here is to talk about nutrition and caloric intake, okay? So let’s say that a doctor evaluates you, and you talk to a nutritionist, and they say, “To be a healthy, thriving person, you need to eat 2,000 calories a day.” And it turns out that you have been eating 1,000 calories a day. You are in starvation mode. Of course, you are not going to be high-performing. You can’t go compete in an athletic competition. You can’t go run a race. You can probably barely run around the block. You’re barely—You’re alive, but you are not thriving. And so we say, “Okay, hey, we’re going to give you 500 more calories. We’re giving you 50% more calories. That’s so many more calories than you’ve been getting.” But it’s still not enough. You’re still only getting 1,500 calories when you need 2,000.

So if we look at this in terms of funding, the conversation is not about, “Well, we gave you more.” More does not equal enough, more does not equal adequacy, and more has nothing to do with equity. And the state’s constitutional commitment has to do with the adequacy of dollars, not, “Well, we gave you more, and we gave you increases every year.” That is completely irrelevant.

JAISAL NOOR: And you bring up an important point that’s rarely raised in the local news in the city. When they’re often just repeating what Governor Hogan has said as news, they rarely mention that in Maryland’s state constitution, which has been upheld by the courts, it is the top priority to adequately fund schools across the state. And Stephen, just this issue of equity, which Jess brought up—

STEPHEN JANIS: Yeah. I think it’s revealing how this is being applied to education in terms of money because, as we all know, in Baltimore, the Department of Justice investigated the police department and found it to be completely dysfunctional, racist, and unconstitutional, but the solution was more money. One of the biggest things people brought up was, “We need more money.” And Hogan supported that. And no one said, “Well, we shouldn’t be giving the police department more money because they can’t spend it, or they’re incompetent.” No one uses those comparisons of money when it comes to fixing the water system.

Why suddenly is the school system singled out as saying, “Money isn’t important,” when every other institution, including law enforcement, which has proven to be racist, is absolutely embraced to say, “Of course we should give them more money,” even though we have evidence that they’ve been wasting or even stealing overtime? So I think it’s just very revealing that this standard is applied to education, but not to other facets of governance.

JESS GARTNER: And to go back to your point about the mismanagement claims, I frankly wish the problem were mismanagement or corruption because mismanagement is actually an easy problem to solve for, right? You just bring in new managers. I mean, mismanagement is a really lazy thing to point at because it has an easy solution.

STEPHEN JANIS: It’s also a little intangible, you know?

JESS GARTNER: Absolutely.

STEPHEN JANIS: I mean, I think if there are points of mismanagement, there have been in all school systems. It’s perfectly fine to get rid of them, but to say systemically, without proof—I agree with you. Sorry, I didn’t mean to interrupt you.

JAISAL NOOR: And there are – online, you see a lot of claims there aren’t audits of Baltimore City, but there’s annual audits, from my understanding.

JESS GARTNER: Yes, they are on OLA. You can go look them up. You can read every page. And are there findings? Yes. But this is part of how the system gets better. You have this body come in, they do an analysis of financial controls, they highlight things that can be better, and then the school system works on fixing them. And those reports take so long to write and publish that often by the time they are available for public consumption, the school district has already checked off a lot of those boxes.

And I will say two other things about audits. One, the findings that have come up in the Baltimore City audit, it sounds really daunting because they’ll say, “Oh, we found 20 things,” but each one of those things could be literally a few dollars, or, “This thing needs an extra signature,” right? It’s not gross management and corruption, it’s like, “Hey, you could use an extra line of approval here,” type of things. And every single thing that’s coming up in those audits are essentially rounding errors on a $1.3 billion budget. I mean, you’re not even getting to single-digit percentage points in terms of total dollars that are coming up in audit findings.

And two, audits have nothing to do with management and efficiency. So I do not understand why people keep bringing up, “Oh, we need an audit. No, we need a forensic audit.” That has nothing to do with saying, “Hey, are we spending dollars in the most efficient way to meet our goals for students?” That is not the purpose of an audit.

JAISAL NOOR: And going back to the point of equity, Stephen, you’ve reported on the issues of trauma and violence in the city. And just the fact that someone would compare student outcomes in Montgomery County, which is one of the wealthiest counties in the country, the average annual income is 90 grand or something. It’s twice as much as in Baltimore City. Of course, the impacts of trauma and other issues are going to affect that.

STEPHEN JANIS: Yeah. I mean, we just, last night, on Monday night, we had a shooting at a school. Twenty-four hours before school opened, there were three people shot and one killed. And as a reporter, I’ve consistently covered shootings at and around school, or students that have been murdered. I mean, we’ve had a series of teens who have been murdered. I think that it is difficult for people to imagine the difference between living in Montgomery County or Howard County, compared to living in Baltimore City for these children who have no other choice. And if you take that out, or you don’t factor that out, I mean, every teacher I’ve ever talked to has said their students are pretty much traumatized. And that is not true. And so that just leads, it gives you—You start with a deficit there, a deficit of psychic pain. And I think that should be accounted for, but of course it does, and they don’t care, so.

JESS GARTNER: I will say on that point, in terms of our expectations for performance, yes, Baltimore City students and families come to school every day having faced a lot of challenges that are different from some of the surrounding counties. That being said, we should absolutely continue to have the highest expectations for performance for Baltimore City students. That doesn’t mean that we should ignore the realities of their lives. That means we may need extra counselors, we may need extra nutrition programs, we may need extra resources for parents, for afterschool programs, for reading intervention, for math specialists. We may need some of those wraparound services to help address those challenges, with the expectation for those high performance metrics in mind.

JAISAL NOOR: And of course, addressing the underlying issue, which is inequality, which is so pervasive across the city and is rarely addressed through policy. And I wanted to end on the issue of what I think is the big elephant in the room in Maryland, which is the issue of privatization. Because Maryland has some of the strongest regulations on public schools. Even charter schools are held accountable under the public school system, and that’s something that Governor Hogan has been targeting, attacking the power of the teacher’s unions throughout his second term now. And so when you have people from the Maryland Public Policy Institute saying New Orleans or DC are examples. And on their website, they listed Michigan during the reign of Betsy DeVos when she was pushing through all these privatization measures. What is the track record with those sort of measures of accountability, which is really a code word for privatization, and the deregulation of schools, and de-unionizing public schools?

JESS GARTNER: So whenever somebody tells me that they think we should privatize our education system, I tell them to imagine Comcast running our education system. And pretty much everybody gets that joke, if you’ve ever had to deal with Comcast in any capacity. So where we got this idea of private equals better, I don’t know. The research certainly does not track consistently with that, particularly on this point of charter schools, which again, our charters are largely public schools. There’s a very small percentage of schools that are actually run by private, for-profit companies. Michigan is an exception, where there are more, but in the vast majority of the country, charter schools are public schools. And like traditional public schools, they have really mixed results. There are some charter schools that are producing phenomenal outcomes for students. They’re providing absolutely wonderful choices for families. They’re doing really inventive, innovative things with curriculum, technology, arts, and they’re a wonderful resource for families and communities. On the flip side, there are charter schools that are atrociously managed. They are harming kids. They are not adhering to laws and regulations. They are not serving special ed students or other vulnerable populations.

And I think that the piece that a lot of people forget when they try to make these comparisons is that traditional public school systems don’t get to not admit a student. They have to educate and provide opportunities and access for every child. That includes if they have severe disabilities and need a special placement, if they have extreme discipline problems, if they have a severe learning disability. There are all these challenges that many schools will try to skirt the rules and play admission games so that they don’t have to provide services to these students, which frankly, are often very expensive in order to comply with the law. There are certain categories of special ed students that require private transportation to school every single day. That is expensive. And there are lots of schools who would love to not have that line item on the books. Your local public school district does not have the luxury of saying, “Oh, no, thank you. We don’t want you in our school system because you will be expensive.”

So people forget that school districts are often putting forth huge sums of money, for the purposes of compliance and regulation, to ensure that every student is getting equal opportunities and access to education. And so, again, it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison. I think that having options for charter schools are, on the whole, a good thing, but they absolutely need to have the same accountability and be upheld with the same rules and regulations for protecting students.

STEPHEN JANIS: That’s one of the things that is really hilarious about this scenario because conservatives purport to like accountability. As a reporter who’s covered public-private partnerships, it’s almost impossible to hold private companies accountable the way you would public resources. You can’t do it. They’re opaque. They don’t have to respond to Public Information Act requests. They can do whatever they want with the money. And there is no way, in any conceivable system, that a private educational institution could be held accountable for their results or for what they do. So it’s kind of weird that these Republicans— I think mainly, they’re just anti-union. I think they can’t stand the fact that working people have some power in the school system. I think that’s the primary thing. That’s the whole thing behind, in my humble opinion, is that there’s an anti-union thrust in a lot of this.

JAISAL NOOR: Yeah, because when you have a strong union, that means one more group of people [crosstalk] that are able to hold the system accountable.

STEPHEN JANIS: You have stakeholders there. You can’t just ignore it. You can’t ignore working people. You can’t ignore people who are educators. And that’s what they want to do. They want to take control like they control everything else.

JAISAL NOOR: Well, I want to thank you both for this really enlightening conversation, Jess Gartner, Stephen Janis.

STEPHEN JANIS: Thank you.

JAISAL NOOR: And we’re going to end with this clip of a public school student, Deshawna Bryant, who is part of the lawsuit being put forward by the ACLU of Maryland, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and public school students in Baltimore City demanding the state uphold its constitutional duty to adequately fund schools.

JAISAL NOOR: I’m Jaisal Noor. Thank you so much for watching.

DESHAWNA BRYANT, BCPSS STUDENT: It has a terrible impact on Baltimore City Public School students because everyone wants to judge us— how they don’t think we’re the best students, how we’re not up there in test scores and everything— but we can’t have the best test scores, we can’t be the best students if we’re not put in the proper environment. If we have to leave every single time it’s cold, if the building has to be let out, or if we have to leave every time it’s too hot to stay in the building, or if our teachers don’t have enough materials to teach us the proper things, it makes us hard to be these students that everybody wants us to live up to be.