Rural and urban voters were divided over support for the accord, says human rights lawyer Dan Kovalik

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

Story Transcript

GREG WILPERT: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Gregory Wilpert, coming to you from Quito, Ecuador.

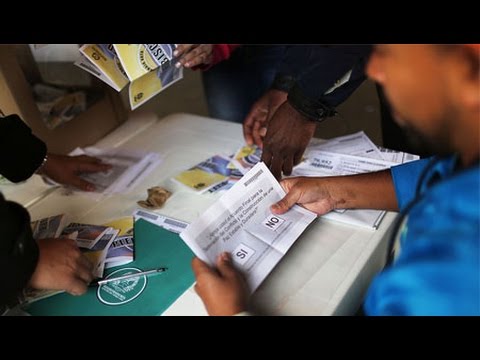

On Sunday Colombian voters surprised everyone when they voted against the peace agreement between the government and the rebel group, the revolutionary armed forces of Colombia, also known as the FARC. The no vote, against the peace agreement, won by razor-thin margin of 50.2 percent. Voter turnout was relatively low, with only 37 percent of eligible voters casting a ballot. The peace agreement which took 4 years to negotiate was meant to put an end to 52 years of civil war that cost over 220 thousand lives and around 6 million refugees. Shortly after the referendum, results were announced, Colombia’s President Juan Manuel Santos as well the FARC’s top commander, Timochenko, gave their reactions to the result. Let’s take a look:

JUAN MANUEL SANTOS: I have given instructions to the chief negotiator from the government and the High Commissioner for Peace to travel to Havana tomorrow to keep FARC negotiators informed on the result of this political dialogue. Now we are all together going to decide between the path that we should take so that the peace, this peace that we all want, is possible and to come out of this stronger. I will not give up.

TIMOCHENKO: The People’s Army, the FARC, profoundly regret the destructive power of those who have sowed hate and rancor has influenced the opinion of the Colombian people. With today’s result, we know that our challenge as a political movement is even greater and we will have to be stronger to create a stable and lasting peace.

Joining us, from Bogota, Colombia, to take a closer look at this surprising result is Dan Kovalik. Dan is a labor and human rights lawyer with a degree from Columbia University law school. He has taught International Human Rights at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law since 2012. Thanks for being on The Real News again, Dan.

DAN KOVALIK: Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

WILPERT: So many polls leading up to the referendum had predicted that the vote in favor of the peace agreement would win by almost like a two thirds majority. In the end though, the no vote won narrowly. Why is that? How do you make sense of this result?

KOVALIK: Well I don’t know why the polls varied. From what happened it did appear to be large abstention. I mean a lot of folks; the voting turnout was poor. Why that was I don’t know. You might’ve heard [inaud.] that maybe there was some military intimidation that kept some folks away from the polls. The other thing I want to mention is that of course there was a hurricane over the weekend which did hit large parts of the Colombian coast. I heard that was the reason in fact that others didn’t show up. So abstention was a problem.

Now in terms of what happened in terms of the vote. What appears happened is for the most part those in the zones of conflict, meaning those in the countryside, peasants, afro Colombians, indigenous, largely voted in favor of the peace accord while those in the city and the expats who have not seen the war in quite some time voted against it. So that seemed to be largely the dynamics working here.

WILPERT: Why would you say, I mean it makes sense to me that people in the countryside who were particularly effected by the civil war would vote in favor of a peace agreement and an end to the conflict as soon as possible. But why would people who live in the cities and presumably less affected be so opposed? How do you make sense of that?

KOVALIK: Again, they would not feel the urgency to end the war and so therefore other things that they’re concerned about for example, one of the things cited was too much amnesty that was built into the accords for human rights abusers. That seemed to be a big issue. That might have been the biggest issue as far as I can tell. So they focused more on that than on the urgency to have peace.

WILPERT: And how do you see the role of President Santos’s unpopularity? He really staked his whole reputation on this peace agreement even though he has apparently a very low approval rating. Something like in the low 20’s or even below that right now. Could it be that Colombians just didn’t trust him to come up with the best possible deal with the FARC?

KOVALIK: I would think that has to be one of the reasons for what happened. One of the Colombians I was talking to yesterday said he believes Santos delivered exactly no votes to the polls. That he has no pull with the Colombian people. So yes, and as you say he has defined himself with this peace process so his unpopularity certainly could not have helped in this situation.

WILPERT: What about the role of former president Álvaro Uribe. He had been complaining against it. Is he somehow seen as a voice of reason or something among the people who are supporting? He seems so far to the right you’d think that he wouldn’t have much influence but seems to have been perhaps not the case?

KOVALIK: Well again I don’t know how much influence he has but obviously he was pushing the no vote and that was what won the day. So one would have to presume he had some influence. I would think that it did make some difference. That he and his others associated definitely pushed very hard for the no vote and I think it had some impact. I do want to say there’s a certain irony there that given that the things he criticized about this peace accord which was essentially as I mentioned, too much amnesty in particular for the guerillas was very much a problem for the peace agreement he made with the paramilitaries back in the mid-2000s which many think was a fake disarmament and that the paramilitaries never really did disarm. And so for him to be talking about that issue is quite ironic but again at the end of the day, he seemed to have some influence.

WILPERT: That was something that I was going to get into is precisely the issue of the amnesty because that’s what his argument was and also the people who apparently voted against it to some extent were arguing against it on the basis of this amnesty for the FARC. Also another group that seemed to be opposed to it was Human Rights Watch who condemned the agreement. You’re a Human Rights Watch lawyer yourself. How do you see that amnesty issue play out? Is it really going too far? Or what is your evaluation and what shape did that amnesty take exactly?

KOVALIK: Well look, it did appear that there was going to be fairly wide amnesty for both government and FARC people. That some leaders would be held accountable but most the rank and file would not. Look I tend to be very pragmatic when it comes to these things. I think that I’ve never seen a peace agreement in the world that didn’t have some type of amnesty and no one would agree to it if it didn’t.

So I just think the idea of getting hung up on that frankly, I think it’s more important to find peace right now, given that people are suffering. And in the end yes, it was up to the Colombian people to decide the calculation on that and I guess they made a decision in a very close vote. Again what is sad is that most affected by it were went the other way and decided peace at this point was more important than in an accord with less amnesty.

WILPERT: And so other individuals, UN Secretary General and Pope Francis supported the peace agreement. Apparently that, I guess, didn’t really leave that much of an impact. But what do you think is likely to happen now as was mentioned in the introduction. Both sides said they’re going to talk to each other again to see how to move forward. From what you can see in the ground having been in Colombia now just for the vote, what do you think is going to be the next step in terms of is it possible in other words to still rescue this peace agreement?

KOVALIK: I think it’s obviously much harder today than it was yesterday to find a peace agreement. They’ve worked 4 years on this. It seems like the government and the FARC are quite sincere in trying to make a peace so yea I think it’s possible. They’re going to go back to the drawing board in Havana and I hope that they find a way to make a deal that’s going to be acceptable.

WILPERT: Okay, well unfortunately we’ve run out of time but thanks so much for giving us your view from the ground there in Colombia and we’ll certainly of course be following the story more as it develops and hope to have you on again.

KOVALIK: Thank you Gregory. Appreciate it.

WILPERT: And thank you for watching the Real News Network.

End

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for The Real News Network are typed from a

recording of the program. TRNN cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.