In his new book “Lost Connections,” Johann Hari argues that depression is more than a chemical imbalance: it’s an illness rooted in the traumas of adverse childhood experiences and an atomized neoliberal society

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

Story Transcript

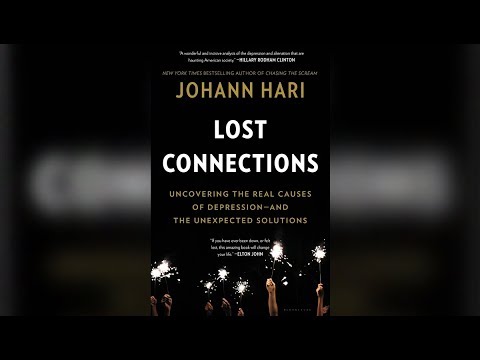

AARON MATÉ: It’s The Real News. I’m Aaron Maté. According to recent studies, depression is on the rise across the US, especially among young people. But do we really understand what causes this illness and how to treat it? Well, a new book argues that depression cannot just be addressed by pills that change our brain chemistry. “Treating depression,” it says, “starts with understanding the key connections between ourselves and the conditions around us, and our families and our societies.” The book is called Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression and the Unexpected Solutions, and I’m joined here in-studio by its author, Johann Hari Hari. Johann, welcome.

JOHANN HARI: It’s great to be with you, Aaron. Thanks very much.

AARON MATÉ: Thanks for coming down. So, I’m struck by one of the first things you take up in the book, which is that the conventional understanding of depression is that it’s an issue of brain chemistry that can be treated by taking antidepressants. That’s how most people see it. You say that’s not the case. Explain what depression actually is and how this focus on brain chemistry is off base.

JOHANN HARI: There’s a real value to chemical antidepressants but it’s not quite what we’ve understood up to now and the place we’ve put it in isn’t quite right. This was a really personal journey for me. There were these two mysteries that were hanging over me that I really wanted to understand. The first was why was I still depressed? When I was a teenager, I’d gone to my doctor and I’d explain that I had this feeling like pain was leaking out of me like a bad smell. I felt very ashamed of it and I didn’t understand it. And my doctor told me a story. This is the ’90s, lots of people were being told this story all over the world. He said, “We know why you feel this way. It’s been proven by scientists. There’s a chemical called serotonin in people’s brains. Some people are naturally lacking it, you’re clearly one of them. We’ll give these drugs; it’ll boost your serotonin levels back to normal. You’ll feel fine.”

And I felt tremendous relief to be told this story. And when I started taking the drugs, I felt a really significant boost. But within a couple of months, this feeling of pain started to bleed back through. I went back, he said, “Clearly we didn’t give you a high enough dose.” Gave me a higher dose. Again, I felt better, again, the pain came back and I was in that kind of rapture until I was taking the maximum possible dose for 13 years, at the end of which I was still depressed. And I thought, “What’s going on here? I’m doing everything I’m told to do.”

The bigger mystery and the much more important one was why were so many more people becoming as distressed as I was? Here in the United States, one in five Americans will take a psychiatric drug in their lifetime. One in four middle-aged women is taking a chemical antidepressant. In any given year, there are far more people who are depressed and anxious who are not taking these drugs. So I thought, why does this, Is this despair really rising? If it is, why? What can we do about it? Seemed to me implausible that it could just be due to a chemical imbalance. But you know, when you have a story about your pain, even if it doesn’t work very well, it kind of structures how you see the world. It’s like putting a leash on a wild animal, at least you know where it is, right? And I was very afraid to begin to look into this.

But I forced myself to go on this big, long journey. It ended up being a really long journey, over 40,000 miles, interviewing the best scientists in the world about what really causes depression, anxiety and what really solves them. And the first thing I learned, which was by far the most painful because losing a story is very painful, is that story my doctor told me is not true. Professor Andrew Scull at Princeton University says it is deeply misleading and unscientific to say depression is just caused by a chemical imbalance. Dr. David Healy, one of the leading British experts, says you can’t even say that story’s been discredited because there was never a time when it was credited. There was never a time when half of the scientists in the field believe it.

This idea that depression is just caused by a chemical imbalance is not true, but that doesn’t mean there’s no value in chemical antidepressants. There’s some value, we can measure this. So, depression is measured by something called the Hamilton Scale. I’ve always felt sorry for whoever Hamilton was that we basically remember him by having miserable people. It goes from one, where you would be dancing around in ecstasy or on ecstasy, to 51, where you would be acutely suicidal.

To give you a sense of movement on that, if you improve your sleep patterns, you will gain six points on the Hamilton Scale. If your sleep patterns get worse, say you have a baby, you’ll lose six points on the Hamilton Scale. On average, according to one of the best experts on this, Professor Irving Kirsch of Harvard Medical School, chemical antidepressants move people 1.8 points on the Hamilton Scale. Important to say a few things: that’s an average; some people get more, some people get less. And the most important thing to say about that is 1.8 points is better than nothing, right? It’s more than a placebo.

Some of my closest relatives still take chemical antidepressants and I’d never urge them to stop because to some of them, that 1.8 points – which is a real gain – outweigh the side effects or the drawbacks. But the more interesting thing to me was to realize, firstly, that 1.8 points doesn’t lift most people out of depression. It’s a little boost but it doesn’t solve the problem. And I then began to learn, according to the World Health Organization, the leading medical body in the world, there are in fact causes of depression-anxiety in the way we live. So, I then went and did a lot of investigating this, and I learned the scientific evidence, the nine causes of depression and anxiety, two are biological and seven are in the way we live, some of which have really risen. And I began to realize that opens up a whole different way for us of thinking about the problem and of thinking about the solutions.

AARON MATÉ: Before we get to that, how is it then that we became so dependent on thinking that taking pills would be the answer? You explore that in talking about how drug companies have had a monopoly not just on the market, but also on the publication of their research.

JOHANN HARI: Yeah, there’s a few things going on. The easiest thing to blame and they have some responsibility, is big pharma. I don’t actually think that’s the main reason, I’ll come to the other reason in a minute. But in terms of big pharma, there’s no dispute about this now. Big pharma massively exaggerated the effects of these drugs. There are real effects but big pharma massively exaggerated and this is established in a really important court case in New York state when Eliot Spitzer was the Attorney General.

So, we all know if you take selfies, you take 30 selfies, and in my case you get rid of the 29 where you don’t like the double chin, and you use the one remaining one where you look all right as your Tinder profile picture. It turns out the drug companies basically did a very similar thing with the scientific studies. They commissioned enormous amounts of scientific research. They junked all the studies which showed a mild effect, and they only published the ones that… So, for example, there was one study where they studied 247 people for the effects of Prozac. They only published the results for 27 of them who, unsurprisingly, were the 27 who worked. So, there was this huge exaggeration of the effects because people will remember, in the ’90s we were told things like these drugs would make you better than well, right? You’ll notice you don’t ever hear that anymore because no one claims that anymore. So, a lot of these claims have fallen away and that’s one reason I actually think is the main one.

I think … how would I put this? I don’t say this with any judgment because I feel it about myself and I felt it about myself. We live in a culture that has completely devalued the idea that there are social causes of anything. When I was a kid, Margaret Thatcher famously said, “There’s no such thing as society, there’s only individuals and their families.” And I was acutely depressed for 13 years and it never occurred to me that there were any social causes of my depression in my environment, right? I never liked Margaret Thatcher, as you can probably guess, but I was a factor to my own pain. In this neoliberal landscape we live in where we’re told everything is about the individual and the only alternative is there’s a problem with their biology, the idea of social causes is like speaking Aramaic or something. People just don’t know what the hell you’re talking about.

So, when the World Health Organization says, as they said in 2001, mental health is produced socially, it has social causes, it’s a social indicator and it needs social solutions as well as individual solutions. We’ve gotten so out of thinking in social terms people are just like, “What the hell does that mean?” It just sounds bizarre. So, I think it’s partly this consumerist culture that’s been trained to think the solution to everything is to go shopping will want a solution to its pain that is like swallowing a pill, and that’s how I felt for a really long time. Problem is, that approach gives some relief but doesn’t solve the problem.

AARON MATÉ: I want to stress that because I think in looking at how your book was received, a lot of people have misrepresented your argument. You’re not saying that people should not take antidepressants. I want to say for myself that I’ve taken them and they’ve helped me a lot. So, I also don’t want to be suggesting that their impact has been overblown. But I think what you highlight is that they’re just not the only solution, and that they’re in some ways a surface solution because they don’t get to the underlying pain that causes depression. So, let’s get to some of the real causes of depression that you think are overlooked. You mentioned nine. What about ourselves? What about the human mind and human development did you learn that most explains how our conditions around us can led to depression?

JOHANN HARI: There were so many examples. One that really struck me, that has resonated with a lot of people is I noticed a lot of the people I know who were depressed and anxious, their depression and anxiety focuses around their work. So, I started to think what’s the evidence about how people feel about their work? Are my friends unusual? And I discovered a really incredibly in-depth piece of research by Gallup, the opinion poll organization, it took years. They found out how people in our culture feel about their work. What they found is 13 percent of people like their work most of the time. 63 percent are what they called sleep-working, sleepwalking through their day. They don’t like it, they don’t hate. And 24 percent of people hate their work, fear it and dread it.

I was quite taken aback by that. 87 percent of people don’t like the thing they’re doing most of the time, right? I started to think could that have some relationship with the way we feel in our mental health and our emotional health. I started to look around at the evidence of this and I learned an incredible Australian social scientist who I got to know, Professor Michael Marmot, had discovered the key to what causes depression at work. It’s not the only thing but it’s by far the biggest. If you go to work and you feel controlled – so you have low or no control – you are significantly more likely to become depressed. You’re actually significantly more likely to have a stress-related heart attack.

And I think this relates to something that connects a lot of the causes of depression-anxiety. I learned about not all of them, which is everyone watching this knows that you have natural physical needs. You need food, you need water, you need warmth, you need shelter, also clean air. If I took those things away from you, things would go real wrong, real fast. There’s equally strong evidence that human beings have natural psychological needs. There are things you need to be a mentally healthy person. You’ve got to feel you belong. You’ve got to feel your life has meaning and purpose. You’ve got to feel that people see you and value you. You’ve got to feel that you’ve got a future that makes sense. And our culture is good at lots of things, but we’ve been getting less and less good at meeting people’s deeper underlying psychological needs.

So, if you think about that in relation to work, if you’re controlled over time, you can’t feel that your life has meaning. You can’t create meaning out of your work. So, when I was looking at that I started to think wasn’t antidepressant for that? What could deal with that? And I actually misunderstood what Professor Marmot was telling me at first. I thought he was saying, you’ve got this fancy elite, the 13 percent who are going to have jobs they like and everyone else is just condemned to be unhappy. And I thought about my dad who’s a bus driver, my brother who’s a delivery guy. Wait, are we just saying that they are being condemned to unhappiness? Professor Marmot said to me, “No, Johann, you’re not listening to me. It’s not the work that makes you depressed, it’s being controlled at work.” And actually it was here in Baltimore that I discovered how differently we can think about this.

So, I came here to meet someone named Meredith…. Meredith used to go to bed every Sunday night just sick with anxiety about the week ahead. She had an office job. It wasn’t the worst office job in the world. She wasn’t being bullied or anything, but she just couldn’t bear the thought that this was going to be the next 40 years of her life. And one day, with her husband, Josh, she embarked on an experiment. Josh had worked in bike stores since he was a teenager here in Baltimore. It’s controlled work, it’s insecure, very low rates at work. And one day, Josh and his colleagues in the bike store had just asked themselves what does our boss actually do? They didn’t hate their boss, he was quite a nice guy. But they were like, we fix all the bikes.

They decided they would set up a bike store, it’s called Baltimore Bicycle Works, that runs on a different principle. They don’t have a boss. It’s a democratic cooperative. So, they take the big decisions together, they share the profits, they share out the good tasks and the crappy tasks so no one gets stuck with the stuff that makes you feel miserable. And so they re-established control over their workplace collectively. And one thing that was so fascinating, which is completely in thinking with Professor Marmot’s findings, is how many of them talked about being depressed and anxious in their previous workplace and not being depressed and anxious in this new workplace. And as Josh said, there’s no reason why any business should run as a corporation. This is a very recent innovation in human history, this institution that makes us feel depressed and controlled and humiliated. Every workplace can be democratic. Imagine how many people you know who today feel terrible who’d feel very differently if they knew that tomorrow they were going to a workplace they controlled with their colleagues.

AARON MATÉ: No argument there. But the question is, well, two questions there: one, not everybody can replicate the act of starting a bike cooperative. It’s just not possible in this capitalist society. Even if it’s 100 percent true that capitalism breeds misery, I have no argument with that. But the second question is, not everyone who is not in control of their work and who is doing work that’s not meaningful to them gets depressed. So, that would lend itself to the fact that work is not obviously, and you weren’t saying that work is the root cause of depression.

JOHANN HARI: Sure, it’s one of the nine causes.

AARON MATÉ: It starts earlier. And you talk about this in the book that actually when we’re young, for many people it starts with actually a loss of power, a loss of feeling safe in the home environment. Why don’t we talk about that?

JOHANN HARI: Just to say, just to finish on the thing about the democratic cooperative. So, you’re totally right to say not everyone can do that. One of my closest relatives is a really struggling, single mother who gets home at end of day and collapses and is struggling to pay the rent, I don’t say to her your job is to democratize your workplace. It would be grotesque. This isn’t an argument for individual change. It’s an argument for collective change. Part of the problem we have is we’re locked in American culture in this kind of false binary, we say something is either a biological flaw, or it’s up to you, buddy, on your own to fix it. And what I’m arguing is we need social change that actually changes everyone, that frees people up to make the changes that they currently can’t make on their own.

AARON MATÉ: But until that social change happens, I guess is my question is what can people do on an individual level short of a revolution, short of a workers cooperative? And I guess the reason I bring up the role of childhood here and child development is something you talk about, which is that understanding that has not been a focus of depression treatment in many western circles. The answer there is going to give people pills. But you talk about actually addressing that, addressing one’s background, one’s own inner pain, can help be a pretty big remedy.

JOHANN HARI: Yes. This was the hardest thing for me to look into for the book for reasons I’ll explain. And your dad, Dr. Gabor Mate, has done incredible work on this and is a real international hero in it. Looking into this really made me realize one of the reasons I had clung to the chemical imbalance story about depression even though in my heart I knew it couldn’t be enough. So, it’s going to sound like I’m telling a story about something completely different but stay with me.

In the mid-1980s, a guy called Dr. Vincent Felitti I got to know obviously later, was commissioned by Kaiser Permanente, a not-for-profit medical provider in California, in San Diego, to solve a problem. They had a hugely expanding obesity crisis in California as they did everywhere else in the United States at the time, and it was a massive driver of medical costs and they were like, nothing they were trying was working in reducing it. So they gave Vincent a pretty big budget and just said do blue skies research and figure out what the hell is going on here.

So, Vincent started working with a group of about 350 extremely obese people, people who weighed more than 400 pounds. And one day he had this kind of maddingly simple idea. He thought what would happen if they just stopped eating and we gave them nutritional supplements for the things that they would lack? Would they just lose loads of weight? So, obviously under extreme medical supervision, these 350 very obese people just stopped eating. And it turns out in one way it works. They lost huge amounts and started living off the fat stores in their body. As the months passed, they lost huge amounts of weight. But then something happened that no one had anticipated. Give you an example.

A woman who I’m going to call Susan to protect some medical confidentiality, Susan, one day she’d gone down from more than 400 pounds to 138 pounds and one day she just freaked out and starts gorging and starts putting huge amounts of weight. And Vincent called her in and said, “Susan, what happened?” Turns out something had happened that had not happened to her in many years. When she was extremely overweight, no men had ever hit on her. And a man had hit on her and it really freaked her out.

And Vincent continued this conversation and he said, “When did you start to put on weight?” It was when she was 11. He said, “What happened when you were 11 that didn’t happen when you were nine, didn’t happen when you were 13? Why then?” And she said, “Well, that’s when my grandfather started to rape me.” And Vincent began to look into this. He discovered that 55 percent of the people on the program had begun to put on weight after being sexually abused. What he discovered is this thing that looked like a pathology, their obesity, actually made sense. As Susan put it to him, “Overweight is overlooked and that’s what I needed to be.”

So, he wanted to figure out more about this. This was a relatively small study; it was 350 people. So, you have the huge study funded by the CDC, the Center for Disease Control, this is where depression comes in. Everyone who came to Kaiser Permanente in the next year for any kind of medical care – broken leg, migraines, anything – got given two sets of questionnaires. First asked, did any of these bad things happen to you when you were a kid: neglect, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, that kind of thing? And the next 10 asked, “Have you experienced any of these problems as an adult: obesity, addiction?” And at last minute, they added depression. When the CDC calculated out the figures, they were astonished. For every category of childhood trauma that happened to you, you were radically more likely to become depressed and anxious. In fact, if you’d had six of those categories, you were 3,100 percent more likely to have attempted to attempted suicide as an adult.

I’ll get to the positive news about this in a minute because I know it sounds pretty bleak. I found this very challenging because when I was a child, I had experienced, my mother had been very ill, my dad was in a different country, and I would experience some very extreme acts of violence from an adult in my life. I clung to the chemical imbalance theory partly because I didn’t want to give that any power over my life. I felt a lot of internalized shame about and I just didn’t want to think about it. And I found it very challenging when I went to spend time with Dr. Felitti in San Diego. I remember going and walking on the beach, and spitting into the ocean and being really angry that he’d made me think about this. But the next stage of his research I found incredibly encouraging, which was once people had indicated they’d experienced these childhood traumas, the doctors were told next time there person comes in, just say a script to them.

The script was, “I see that when you were a child you were sexually abused, whatever it was. I’m really sorry that happened. That should never have happened to you. Would you like to talk about it?” And a lot of people said, “No, I’d rather not talk about it, thank you,” and a lot of people did want to talk about it. And they talked on average for five minutes about it and at the end of that the doctor said I can refer you to a therapist to talk more about this if you want. Just that act of five minutes of an authority figure saying this should never have happened to you led to a really significant fall in depression and anxiety over the following year. People who were referred to a therapist had a 50 percent fall.

And what that tells us is that releasing shame is incredibly, we know, for example from the AIDS crisis, openly gay men died on average two years later than closeted gay men even when they were diagnosed at the same time. Shame destroys people. There’s a reason why almost all human societies got some form of confession. Turns out Catholic church does had something right every now and then. So, back to me, and again, when I sort of absorbed that, how unethical it was to tell people it’s just a chemical imbalance in your brain, right?

AARON MATÉ: I want to quote for you something that I found very persuasive, where you’re writing about actually how the shame develops. I think understanding how that happens is very important to overcoming it. You say, “When you’re a child,” and you’re speaking about childhood experiences that are painful. “When you’re a child, you have very little power to change your environment. You can’t move away or force somebody to stop hurting you, so you have two choices: You can admit to yourself that you are powerless, that at any moment you could be badly hurt and there’s simply nothing you can do about it. Or you can tell yourself it’s your fault. If you do that, you actually gain some power, at least in your own mind. If it’s your fault, then there’s something you can do that might make it different. You aren’t a pinball being smacked around a pinball machine. You’re the person controlling the machine.”

I found that really powerful because it tells people that the shame that they carry inside themselves and their tendency to maybe blame themselves for things, for their own issues, actually results from them – when they were too young to know – trying to gain some power. I wonder if you can talk about that.

JOHANN HARI: It’s not the easiest thing to talk about but I think this connects with lots of the things that I learned, which is so many of the things that we think of as pathologies, as like malfunctions, are in fact functions. If you think about what I was told by my doctor, I was told that my depression was just a kind of sign that I was internally biologically broken. Actually, one of the things I learned from so many of these people I got to know and from the arguments at the World Health Organization is, if you’re depressed, if you’re anxious, you’re not crazy. You’re not a pathologized person. You’re not a machine with broken parts. You’re a human being with unmet needs.

And there’s a really powerful illustration of I think how we got this so wrong. It was something that was discovered in the 1970s. In the ’70s, there was this, this weird thing was discovered about depression that was shunted to one side. So, psychiatrists in the US for the first time laid out a checklist for doctors to use to diagnose depression. It’s kind of an obvious checklist, 10 points, things like does the person feel worthless. And it says if the patient is experiencing more than five of these symptoms for more than two weeks, you should diagnose them as mentally ill, right?

So, this checklist goes out all over the United States. After a little while, psychiatrists start to come back and go, “There’s something a bit awkward about this. Using this checklist, we should diagnose every grieving person as mentally ill because all grieving people show these symptoms.” So, the psychiatrist was like, “Well, that’s what we intended,” so they created something they called the Grief Loophole. It says if you show any of these symptoms and you’ve lost someone you love in the past year, they’re not mentally ill. Don’t worry, don’t diagnose them.

So, psychiatrists start using that, but that raised a really awkward question. So wait a minute, what we’re saying is depression is just a brain disease to be identified on a checklist, except in one instance uniquely in human behavior when it’s a reasonable response to life. But why is losing someone you love the only reasonable response? Why not if you’ve lost your job or if you’ve lost your home, or you’re stuck in a job you hate for the next 20 years, or you’re acutely lonely, or all sorts of factors? But what that meant as Dr. Joanne Cacciatore, who’s one of the amazing experts on this that I interviewed, said to me, “That requires you to think about context. That open blasts a hole in the whole system. It requires a whole system overhaul.” She says that actually depression and anxiety are not pathological malfunctions, they’re legitimate signals that something’s gone wrong in the culture.

So, the response of the psychiatric authorities was just to get rid of the grief exception. It doesn’t exist anymore. So, now if your child dies at 10:00 a.m., you can be diagnosed that morning with depression and anxiety and mental illness. You can be drugged. In fact, Dr. Cacciatore has shown 32 percent of grieving parents are drugged in the first 48 hours. And what that shows is, as Dr. Cacciatore puts it, we just don’t understand pain. Grief is not a malfunction. We grieve because we’ve loved someone.

AARON MATÉ: It’s a response.

JOHANN HARI: It’s a tribute to our love for that person. And in a similar way, depression is a form of grief for our own lives not going right. Now when someone we love dies and there’s grief there, all we can do is hold the surviving people and love them. But with grieve for our own lives, the solution is that collectively and together we can change our lives so it meets our needs more deeply.

AARON MATÉ: But back to what you said here about shame being a response to your environment and a way for the young child to gain control. I think that, to me, also helps explain why depression is so hard to shake because if depression is informed by a perception that a bad experience is the own person’s fault, and if that is, the reason that they have that perception is an attempt to gain power and some control over a confusing situation, then it’s given them an identity. It’s helped them survive. And so, when that grows with them into adulthood and they’re trying to shake that, I wonder if that helps explain why depression is so hard to shake because actually back when you needed it, back when you needed an explanation for an adverse experience, it gave you power.

JOHANN HARI: That’s a really astute point. I think there’s also something else going on there, which is again, one of the things that connects so many of the causes of depression-anxiety that I write about in “Lost Connections” is a loss of control. So, we talked about loss of control at work, loss of control when you’re treated appallingly as a child. And it’s interesting to look at experiments that are about giving people back control.

So, there’s a really fascinating one in Canada in the 1970s, and the Canadian government chose seemingly at random a town called Dauphin. It’s in Manitoba. And they said to a big load of people in this town, “We’re going to give you from now on in monthly installments a guaranteed basic income.” It was the equivalent of $15,000 a year in today’s money. Said to these people, “There’s nothing you have to do in return for this money and there’s nothing you can do that means we’ll take it away. It’s just we want you to have a good life.” And this was monitored by a wonderful social scientist I didn’t speak with, Dr. Evelyn Forget, many really interesting things happened, but one of the most fascinating is there was a really significant fall in depression and anxiety. In fact, severe depression and anxiety that was so bad people had to be taken to hospital and shut away, fell by nine percent in just three years. And as Dr. Forget said to me, “That’s an antidepressant, right? Universal basic income is an antidepressant.”

What does that relate to? This loss of control that’s happened across the culture was one of the big factors driving Trump, driving Brexit in my own country, as you can tell, I’m British. This loss of control that’s happened and this loss of agency which is not imaginary and it’s not a pathology, people are really reacting to a genuine loss of control in their lives. We have to look at solutions that are about giving people back security and agency.

There was an incredible study that showed people who have an income from property are 10 times less likely to develop an anxiety disorder than people who have no income from property. Half of all Americans haven’t been able to put aside $500 for if a crisis comes along. You’re talking people living with extraordinary insecurity and extraordinary loss of control and agency in their lives, which helps to explain so much of the anger that people are expressing, which again, is totally legitimate anger. I don’t agree with, obviously as you can guess, I’m strongly against Donald Trump. I think we have to understand why people try to send this signal of we want to burn the house down, it’s because their psychological needs are not being met. There are many things going on. This is not the only one of course but we have to understand this loss of control and we have to be looking for strategies that are about restoring control to people.

AARON MATÉ: The book is Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression and the Unexpected Solutions. Johann Hari, thank you.

JOHANN HARI: Cheers, Aaron. Really appreciate it.

AARON MATÉ: And thank you for joining us on The Real News.