Nation Senior Editor Atossa Araxia Abrahamian wrote a lead article, ‘The Inequality Industry,’ which takes a deep dive into its history, the present political struggle and the future

Story Transcript

MARC STEINER: Welcome to The Real News Network, I’m Marc Steiner. Great to have you with us.

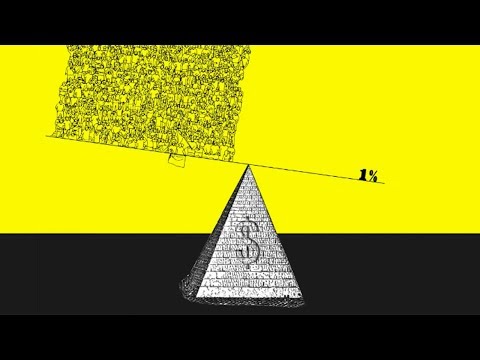

Just seven years ago or so, income inequality was not the buzzword of the resistance or the movement as it is now. As our guest writes, it was a niche field in the world of academia and social economic analysis, not deemed to be that important to really analyze and study deeply. But now, income inequality is at the center of the storm, used by right wing populists like Trump and others around the globe to marshal the anger and frustrations of many workers. But martialing is not done against the wealthy or the powerful, but creating enemies out of people like themselves, just people of color.

Income inequality is also a battle cry for progressives, radicals and revolutionaries who see what the neoliberal state and the conservative political worlds have done to dismantle all the social underpinnings put in place to end poverty and save capitalism. That’s true from Nixon through Reagan, especially Reagan and Clinton, and to all the presidents since. Growth, rather than equality, became the operative system championed in the United States. Growth was the answer, and relative equality would be established in its wake, people said.

Well, senior editor at The Nation, author of The Cosmopolites: The Coming of the Global Citizen, her cover story is The Inequality Industry in this issue of The Nation, joins us now. And it’s a pleasure to have with us Atossa Araxia Abrahamian. Welcome, good to have you with us.

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: Thanks so much for having me.

MARC STEINER: So, to me, this is really an important article. And I just want to kind of take a step back a bit and talk a bit why you thought it was so important to put on the cover and what you think we’re facing.

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Join thousands of others who support our nonprofit journalism and help us deliver the news and analysis you won’t get anywhere else:

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: Yeah, so here at The Nation, we were thinking about how to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the financial crisis. And there’s been so much written about this already, the state of the world, the rise of populism, the state of the markets, which are actually doing very well. And I thought, well you know, one really good thing to come out of the crisis, or I thought, and I still think it is rather a good thing, is that suddenly everyone really cares about economic inequality. You mentioned income inequality a few times, but I just want to reiterate that it’s not only income, it’s economic inequality in the sense that it includes wealth, income, assets and so on.

MARC STEINER: Right, absolutely.

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: And so, Americans and people around the world actually are vastly unequal. It took the crisis for the media, the public, politicians, thinkers, pundits to realize this. And around 2010 in the aftermath of the crisis, we started seeing these shocking numbers. So, this isn’t in the story, but between 1993 and 2010, the top one percent in the United States saw their incomes grow by fifty-eight percent. Everybody else saw their incomes grow six-point four percent. Also, in 2010, three hundred and eighty-eight people, that’s people, owned half of the world’s wealth. So, these are really shocking numbers, and they roll off the tongue. They’re just- you’re taken aback.

And I started noticing more and more of these stats pop up after the crisis. I think that a really important moment for this awareness was Occupy Wall Street. You saw the rise of this concept of the one percent that was not prevalent before. You saw posters, you saw marches, you saw people saying, “How did we get here?” And as a result, the interest around economic inequality grew, not just on the streets but in academic departments, at institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. You had central banks looking into this, you have economists everywhere at the U.N.

And what happened there is that this gave rise to what I call an inequality industrial complex. All of this money, all of this research being funneled into the study of inequality. And again, that seems like a really good thing. But what we wanted to do here at The Nation is take a step back and say, “Is this really progressive, who is benefiting from this whole scene, what is the research showing and how has it significantly changed the conversation?” So, the article was a result of that kind of meta-research on inequality, and we found some pretty interesting stuff.

MARC STEINER: And again, I think it’s important here to talk a little bit about history, as you do in your article, which is to talk about how we got to the place that we’re in at this moment. You can take this back to the 1930s and the Great Depression, when Roosevelt was desperate to save capitalism and thought the only way was kind of to deal with the question of inequality, in that day during the Depression, and set up things in motion and set up organizations and set up laws that would try to end poverty, put people to work. Then World War II came, and we saw this kind of wave of seemingly to caring about this up until the 70s, when a real shift took place under Nixon. And in wake of the antiwar movement, the Black Panthers and more, that saw this kind of conservative shift that really took hold in Reagan and then through Clinton. So, I mean, talk about what happened there, and what brought the nation to want to deal with the beginning, and why we’ve ended up where we are now.

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: So, this is a caveat. This is very broad strokes.

MARC STEINER: Yes, that’s cool.

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: We last saw an all-time time peak in economic inequality in the U.S. around the time of the Great Depression. And after that time, in rebuilding the economy in the years that followed, which actually it was a wartime economy for many of those decades, the economy was growing and recovering from the recession, from the Depression, rather. But there was also war. There were also social movements. There was the beginning of the welfare state. And during this time, Americans and America as a country experienced economic growth, but the gains were distributed somewhat equitably, right? Organized labor started to gain power. Deficit spending rose. And this is a period that economists and historians call the Great Compression. And as a result, inequality fell since the Depression through to the 1970s.

What we saw in the 1970s is now a pretty familiar narrative, the narrative of deregulation and neoliberalism. Unions had less and less power, cuts to social services under Bush and under Clinton created a more unstable situation for working Americans, for lower class people. And while social movements did raise awareness of other types of inequalities, gender inequality, there was a civil rights movement, this is all really important stuff, economics didn’t really catch on in the same way. And that’s because there’s a persistent myth, very closely linked to this notion of trickle-down economics, that if the country is experiencing growth, that’s the important thing, and that this rising tide, that this growth is going to lift all boats, that everyone is going to end up better off.

And the general- the gist of this way of thinking is that as long as everyone is less poor, we’re okay. It doesn’t matter if the rich are a million times richer than the poorest person as long as the poorest person is getting less poor. Now we know that this creates really complicated situations in the country, because when rich people have so much more money, and when the political system is rigged to benefit people with so much more money, they have more power, right? They have more power over politics, they have more power over what the private sector does, they have a role in shaping laws. When the private sector is unduly powerful, it creates political conflicts of interest- well, not for them, but for the rest of us.

And basically, now we know- and this wasn’t really acknowledged fully before- now we know that when rich people have way more money than everybody else, it not only creates economic inequalities, but also political ones and social ones. And a lot of the research that’s come out of this inequality industrial complex is aimed at showing how this happens and showing the broader social ills that come out of a vastly unequal society.

MARC STEINER: So, I want to explore for a moment here where we are politically and what it means about how people use this moment of deep inequality for their own political purposes on many levels. Let me start for our listeners here, to watch for a moment President Barack Obama talking about this income inequality and wealth inequality in America, and what it means for him. And then we’re going to parse through why there are so many different ideas about what this means and how to address it.

BARACK OBAMA: A dangerous and growing inequality and lack of upward mobility that has jeopardized middle class America’s basic bargain, that if you work hard, you have a chance to get ahead. I believe this is the defining challenge of our time, making sure our economy works for every working American. I am convinced that the decisions we make on these issues over the next few years will determine whether or not our children will grow up in an America where opportunity is real.

MARC STEINER: So, one of the things here that really hit me about your piece, and you also refer to this particular speech in your article that Obama gave, is what are we looking for here? I mean, when you look at the neoliberal government, they’re looking to not necessarily eliminate poverty completely, but to make sure people think they can get ahead, and that it’s okay if folks, as you write, get wealthy and rich as long as people aren’t left completely behind. And you see the right-wing using this here and across the globe as a way to get workers and others to come to their side, to say it’s someone else’s fault and we’re going to need a more authoritarian government make this happen and to change things. And then you’ve got the left, who’s working on the same inequality issues. And the question comes up, as you raised in your article, are we talking about really creating equality or just making us less unequal?

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: Yeah. So, just to recap the narrative, the sort of conventional wisdom went from inequality doesn’t matter because growth matters to a version of that that stipulates that inequality is bad because it’s bad for growth. So, it’s different, but it’s kind of the same, right? Growth is still the operative term here. The point is to have more growth, and maybe we need less inequality to have more growth. I think that this is a convincing argument insofar that it is apolitical, everyone can get behind growth. You know, technocrats love growth, politicians love growth, workers love growth, unions love growth and bosses love growth. I can’t find anyone who is really opposed to growth except a small group of environmentally minded people.

And so, it’s a very easy sell politically. And you can see why the IMF has started saying things like this, you can see why Obama says things like this. The problem is that it doesn’t really make a case for egalitarianism and it doesn’t really make a case for equality in moral terms. And I think that that is a really crucial part of this discussion that we’re not having right now. If we’re just arguing for less inequality on instrumental grounds, I think that people are going to be left out, right? Because if you get sort of enough equality, leave a bunch of people out and you still get growth, then you can say, “Oh, it’s okay, we have growth, so forget about those people.”

And we’re at a time when Americans feel so unequal. You know, I mentioned this in this story, but women feel unequal, African Americans feel unequal. Heck, even white men feel unequal, even white men feel discriminated against, right? So, there’s clearly a moral case to be made for equality, and I think that we’re really missing out on that. And by only focusing on inequality, I think it really does highlight the differences rather than something that we should be aiming for as a common goal.

MARC STEINER: So, the question does become what we mean by a political platform and ideas about equality and how we define that equality and what that means. I mean, as you allude to in your article and you say in your article, in many ways the efforts taken by the Western governments- different in Europe than they have been in America for reasons, maybe the power of unions and also the depth of racism in our country that blocked what could have happened in the United States. But even there right now, you’re seeing in Europe and the United States, people kind of attacking the system, the inequality growing in all these societies. So, the question is, what does equality mean as a political struggle, and how do you see that developing, how do you see that conversation happening?

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: Well, I wish I had all the answers.

MARC STEINER: No, I don’t expect you to.

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: I think it’s about power, right? It’s not just about tweaking the tax code so that rich people give a little bit more of their money to people who are less rich. Because then, you have to decide how you’re going to spend the money, and that’s really political too. If you just tax the rich and use the money on war, okay, maybe on some level it will redistribute some money, but I don’t know if that’s really a progressive policy. What you want is to, I think you have to take money out of politics, a decision like Citizens United is a catastrophe, it really exacerbates how much power wealthy people have over the political process and politicians. So, that’s a start. Don’t think that’s going to happen at the rate we’re going.

I think that giving more power to labor unions or people who are collectively organizing, whether it’s in their neighborhoods, whether it’s in their workplace, whether it’s on the state level, giving people more power and more say in what happens. And that’s really hard to do, right? You have to start from the ground up, but you also have to have deep structural change in the political system. And I didn’t want to discount redistribution, because I do think it’s important. But that also has to happen from the bottom up and the top down. Higher wages, better benefits. All of these things make it easier for people to not be poor. And then when they stop being poor, then they can start being better, they can start doing better and start working their way up.

By the same token, I really think that rich people, and some of them acknowledge this and some of them don’t, something’s got to give. Some of that money has got to go to the bottom. Some of that money has got to be invested in public programs. The president of the Ford Foundation I spoke to for this story, and the Ford Foundation has started to pivot towards putting most of its resources to studying inequality and funding people who do so. Even the Ford Foundation are talking about this. They’re a really, really mainstream organization. So, these things are really important to talk about. We’ve got to start talking about them now. We’ve got to keep up the hard work.

It’s really hard with the Senate and Congress entirely controlled by Republicans whose tax bill is doing the opposite of all of the things I’m mentioning. I mean, this is a classic case of redistributing wealth to the top. So, it’s an uphill battle and it’s a really, really hard time to be working at passing policies around this issue. But the research there, the enthusiasm is there. Right now, the political will is not.

MARC STEINER: So, I’d like to conclude with a thought that’s pulling from two different sections of your piece in The Nation. So, one is when you talk about Darren Walker, who is leading the Ford Foundation’s pivot around inequality. And the quote was, “I refuse to believe that this is just a natural phenomenon or part of capitalism,” was the quote that you quoted of him in your piece. And then in another part of the piece, you write, in talking about how we end all this, “That might mean pressuring governments to take from the few to give to the many. It might mean more cooperative models of ownership. It might involve burning the whole thing down.” So, to me, those two places in your article are almost at the kernel of people having to wrestle with what we do to address it.

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: Yeah. Two things are going on. I think that the smarter wealthy people, people who are running institutions, people who have a lot of power, are realizing that these levels of economic inequality are destabilizing. That’s part of what the research has shown. It’s bad for society, it’s bad for democracy, and in the end, heads will roll. And that’s part of why there’s so much enthusiasm for reducing inequality from people who go to Davos, right? The World Economic Forum has been talking about this for years, to their great credit. But you also have to realize that this isn’t necessarily a very radical conversation. Reducing inequality is not a radical conversation, necessarily. It can be purely out of self-preservation, historically.

And there’s been quite a good book written about this by Walter Scheidel called The Great Leveler. Inequality has only really fallen in significant ways in countries that have experienced some pretty bad stuff; war, plague, famine, immiseration, these are really equalizers. And so, if we look at history, there’s very little to be excited about when it comes to incrementalism, when it comes to tweaking the tax code, for instance. And so, there is kind of a tension here, right? Do we do damage control and try to reduce inequality inasmuch as possible, so that there isn’t a horrible revolution? Do we let it keep going and see what happens? I’m not convinced either of these are a good solution, but these are kind of the stakes.

MARC STEINER: This has been fascinating. It’s a great article, I appreciate you taking the time with us here at The Real News, Atossa. We’ve been talking with Atossa Araxia Abrahamian, who is the senior editor at The Nation magazine. Atossa, thanks for your work, thanks for being with us, and we’re looking forward to seeing what else comes down the pike with you and your fellows at The Nation.

ATOSSA ARAXIA ABRAHAMIAN: Thanks for having me.

MARC STEINER: Thank you. And I’m Marc Steiner, here for The Real News Network. Thanks for joining us. We’ll be talking together soon.